|

| Seidman Cancer Center Orange Place Beachwood, Ohio |

Wednesday, September 29, 2021

Another Long Day at Seidman Cancer Center

Monday, September 27, 2021

So Where Did My Love of Shakespeare Come From?

If you had told me in tenth grade (when we were supposed to read Julius Caesar) that I would end up loving Shakespeare, I would have laughed in your stupid face. I hated him. I just didn’t understand much of what he wrote. And I couldn’t understand why other students liked him—or pretended to do so.

Same thing senior year when we read Macbeth. Couldn’t do it.

Same thing in English 101 at Hiram College, when once again, we were supposed to read Macbeth. I just couldn’t manage.

And so I planned carefully: The professor who taught the Shakespeare course was on sabbatical the year I could have taken his class (he offered it only every other year). I was so happy: I got to graduate with an English major without having taken a single Shakespeare class!

My first teaching job was in a middle school, so I figured I wouldn’t need to know any Shakespeare. And I was right: I didn’t need to, but it wasn’t too long before I wanted to.

And soon I “needed to” in a very different way. I was hooked.

And I think it started with that old Richard Burton-Elizabeth Taylor version of The Taming of the Shrew, directed by Franco Zeffirelli (1967). I loved that film, saw it several times before I taught it to my eighth graders. Or tried to.

I was still mostly ignorant, you see. Relying on footnotes and quick trips to reference books before class (no Internet then).

But as the years went on, I added more and more to my Shakespeare efforts in class. We played Elizabethan games, ate their food, listened to their music, talked about their clothing and the like. I taught them some history—especially the “cool parts”—the severed heads on London Bridge, the behavior at the Globe, the behavior of the royalty, etc.

Soon, the Bard was consuming an entire 9-week marking period.

I learned that the best strategy was to read it aloud with them, sharing parts. Stopping to clear up a confusion. I saved Act V for after the film (all the Bard’s plays are divided into five acts—though the action was continuous at the playhouses).

Soon I found another film I liked even more—Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing (1993), a film that still moves me (Joyce and I streamed it a few months ago). One strength: the cast. It includes some people who are still notable now—Keanu Reeves, Michael Keaton, Emma Thompson, Denzel Washington, Kate Beckinsale—along with some wonderful English performers: Richard Briers, Brian Blessed, and others.

So I taught it the last few years of my public school career (I retired in January 1997).

Meanwhile, I was reading books about the Bard and his world, reading all the plays and poems and sonnets (memorizing about twenty of the sonnets).

I traveled to England to visit his birthplace (in Stratford-upon-Avon), to London to visit the new Globe (where my son and his sons saw A Comedy of Errors).

Joyce and I went to see every play we could—in Cleveland, Stratford (Ont.), Staunton (Va.—at the American Shakespeare Center). After some years we were waiting to see the last play we had not yet seen, Richard II.

My younger brother called one day and said that play was now running at Shakespeare & Co. in Lenox, MA, not far from where they lived. Off we went. And when the lights came up afterward, both Joyce and I were weeping.

A far cry (!) from Hiram High School.

My obsession really hasn’t waned. Although I can’t go out anymore, I still read books, still revisit the plays, still try to keep those sonnets in my memory. (A bit of a job these days.)

So what hooked me on the Bard? When I realized that I couldn’t read him if I didn’t enter his world (just as he wouldn’t know what-the-hell was going on in 2021 Hudson, Ohio). When I realized the profound truths that resonated through his sometimes unfamiliar words. When I recognized the beauty of his language.

My 1959-60 self would not believe what has happened to him. He would believe he’d turned in the biggest nerd in the world. Whereas I believe I’ve had the greatest education in the world—so much of it coming from a man who didn’t know what electricity is. What a Tweet is. What TikTok is. What ...

Friday, September 24, 2021

Slip-Slidin’ Away

You might remember this 1975 song by Paul Simon? (If not, it’s easy to find on YouTube.)

As I was thinking about it today, I was lamenting my current physical and mental condition and one especially deleterious effect it has had: forgetting.

Just a couple of years ago I had, firmly stored in my memory vault, about 230 poems I'd memorized over the years. I was able to trot them out and annoy friends and family all the time. (I took some pleasure in that, actually—the annoyance.)

It was a bit of work to keep them stored. I had a schedule I adhered to rigorously. I had a set of poems I said on my daily walks to and from the coffee shop, some I mumbled at the coffee shop, sets I mumbled various days at the health club (M-W-F, TU-TH-SAT). I had a set I rehearsed in the morning in the shower (I know, I know).

And so I was able to keep them all in my head.

But my New Life is different: I don't walk or go to the coffee shop; I can't go to the health club.

That leaves home, where I do my best—but just don't have the energy to do them all. Not nearly.

I try to keep the long, complex ones that took me so long to learn ("Kubla Khan," "Renascence," poems by Auden and E. E. Cummings, et al.), but some of the others have been slip-slidin' away the past couple of years.

I do have a complete list I keep on my computer so my survivors will know all that my dead head used to hold. Maybe they’ll be impressed. Maybe depressed. (Why did he waste his time doing that?!)

One comforting thing I have learned over the years: Poems I learned long ago (and forgot) returned quickly when I re-memorized them. “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” for example, which I learned back at Adams Elementary School in Enid, OK, leapt back into my head when I began rehearsing it. As did the opening lines of Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (Hiram High School).

A bit of consolation, I guess.

And I’d wager that most of you who’d loved that 1975 Simon song could not remember all the lyrics now, but if you look at them/listen to the song, they’ll return as quickly as a boomerang.

And to make it easier for you, here’s a link to Simon singing it!

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Reading Anne Tyler #1

I’ve started reading Anne Tyler’s first novel, If Morning Ever Comes, published in 1964 when she was only 22 years old (I was still a student, midway through Hiram College). It takes place in Sandhill, NC, where a young man from there, Ben Joe, is at law school at Columbia and, on impulse, decides to return to visit his family.

And oh what a complicated bunch they are! From a great-grandmother to a baby.

I’ll write more about the book when I finish it.

But it got me thinking of how different the world was when I was a college student. No cell phone; no computers (except the UNIVAC type that filled an entire room—we each carry more power in our pockets these days).

JFK was assassinated in November 1963. The MLK, Jr. speech “I Have a Dream” was earlier in 1963. The world was ready to boil as the Vietnam War was commencing. There was no Medicare or Medicaid. No Voting Rights Act. Etc. There was still de facto segregation throughout much of the South. The cities were ticking racial time bombs.

Born in Enid, Oklahoma, a small city fully segregated, in 1944, I would not speak to a black person till I was in college—where I found out what I had been missing. I felt like an idiot. And I was.

In 1964 I wasn’t sure what I was going to do—or be. My parents wanted me to teach; therefore, I did not want to. I found, because of a couple of wonderful professors, that I loved literature, so I applied to the University of Kansas for their American Studies Ph.D. program. I got in ... but with no financial aid. So ... I couldn’t go.

To appease my parents, I had done my student teaching, had earned my teaching certificate from the State of Ohio in secondary school English.

I’ve told this before, but my critic teacher at West Geauga HS (where I did my student teaching) warned me, “Don’t get stuck in a junior high school!”

But I did. I applied for only two jobs (there was a teacher shortage), and the first one to call me back was in nearby Aurora, Ohio. I interviewed. Got the job (7th grade) and started my career in the fall of 1966.

I was thinking I would stay a year and get the hell out.

Ha!

I stayed a dozen years (earning my Ph.D. at KSU, mostly part-time), married a wonderful woman, and left Aurora at the end of the 1978 school year, having accepted a job as the Chair of the Department of Education at Lake Forest College (north of Chicago).

But I missed middle school kids, and so ...

I’m drifting away from 1964, the year we elected LBJ, captured the Boston Strangler, the Beatles released their first album (on LP, of course), the USSR was our biggest fear, Cassius Clay defeated Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title ... and so much more.

I turned 20 in 1964–impossible to believe that our world was so ... different. Yet in some scary ways fundamentally the same. Divided. So many people certain they were right—about everything. And anger, boiling, that would soon flow out into our streets ...

Saturday, September 18, 2021

I Keep Buying Books

|

| Colson Whitehead (a favorite) |

I have slowed down some, buying books. I told myself some time ago that I really needed to do this. We’re out of room for them, and my memory’s not as good as it used to be. Joyce is now reading a book I read a few months ago, and I remember hardly any of it now. I recall liking it—that’s about it.

I’ve continued with an old, old habit—reading an author’s complete works—a habit I learned at Hiram College back in the mid-1960s, a habit, as I said, that continues to this day. I suppose I could read them on Kindle or get them from the library. But I don’t. I buy them all, all first printings, sometimes signed. It’s kind of a sickness.

A few years ago I quit buying snack-food fiction—mysteries and the like. I buy them on Kindle (a bit cheaper) and read them at night when my energy wanes—which occurs earlier and earlier these days.

I don’t mean to diminish the quality of some of those books by referring to them as “snack-food fiction”: I mean only that I gulp them down, not pausing to take notes or think too much. Books by John Grisham, Scott Turow, and other mystery writers. I admire what they’ve accomplished.

But when I identify a writer I really like (Paul Auster, Elizabeth Strout, Anne Tyler, Maggie O’Farrell, Ian McEwan, and many others) I just have to read it all. I can’t help it.

Right now it’s Tyler. I had not read much of her work, but once I started, I felt that old familiar buzz commence, and off I went into Tyler-land, from which I will not emerge until I’m finished.

This week some new books have arrived by Auster, Ian Frazier, Colson Whitehead, and some others, so I’ll be reading them—and very soon.

Can’t let myself slip behind ...

Tuesday, September 14, 2021

File It!

When I began teaching seventh graders in the fall 1966 at the old Aurora Middle School, my room was number 116. Except for tables and chairs (for the students), a PA speaker, and some blackboards (they were green!), and a teacher’s desk, my room was empty.

Oh, there was a filing cabinet in the back of the room. It was empty.

When I left teaching in 2011, I had accumulated more than half a dozen file cabinets, all chockablock with files; the basement now features other files in plastic storage boxes.

So what happened?

I’ve filed not just handouts and quizzes and tests but enormous amounts of information about the writers and books I taught and/or wrote about. I’ve got an entire filing cabinet devoted to Jack London, another jammed with information about Edgar Poe, another full of stuff about Shakespeare—including programs for productions of all of his plays (all of which we’ve seen).

Whenever I saw in a newspaper anything related to one of “my” writers, I clipped and stored it in the file(s).

There are also keepsakes in there—programs from speeches “my” writers gave, stamps that picture them, first-day covers of those stamps, etc.

And copies of my own publications. I wrote so many reviews for Kirkus (1563), that I’ve hole-punched them and stored them in notebooks. The same with these blog posts, the same with the doggerel I’ve written over the years.

I continued doing this after I retired—stuffing material into folders and notebooks. I had no real reason to do so, or course. I wasn’t teaching ... who would ever know? Or care? But still I forged on.

Until about a year ago when my balance became so bad—and my madness subsided somewhat—that my sanity emerged somewhat victorious. (I still keep these posts in notebooks.)

So now what?

Who would possibly want all that stuff?

Who would want to sort through it all, separating the good, the bad, the ugly? (The “ugly” pile will be alpine.)

I guess it won’t matter: I’ll be elsewhere by then (let’s not speculate about where). And, anyway, for virtually all of us on this earth there is no “forever.” A thousand years from now (assuming we haven’t destroyed the planet) who among us will be remembered?

But last night I was thinking this: In those files—in those cabinets—among those words I still exist. And live. At least for a while.

Saturday, September 11, 2021

I Can’t Do It All ...

|

| Baked yesterday. |

For years I’ve posted on FB a picture of the sourdough bread I’ve baked that week. The pic has become part of the baking—and people have come to expect it, have become worried when I don’t post one.

Now, every few weeks, I do sourdough waffles instead. They don’t take anything like the energy that the bread does, and I can wait for a later day in the week to bake them, a day I feel strong enough to do it. A day when Joyce is available—for without her? No baking at all.

We put the waffles off till Friday this week (too busy and whupped to do it earlier). We kind of had to do it—or throw away the sourdough (not the starter—that lives and lives and lives, as long as I feed it once a week).

Our refrigerator is just too small to hold two large bowls, one with the waffles-that-aren’t-yet-baked, the other holding the dough we fed on Saturday and will use on Sunday to bake our bread.

So ... we mixed the waffle batter this morning (Friday); we’ll warm it up; we’ll bake; we’ll eat one waffle apiece tonight and freeze the others to give to our son and his family. The younger grandson, Carson, especially loves them and sometimes (I hear from one of my ubiquitous spies) sneaks downstairs at night to steal one. (Reminds me of someone I knew very well about, oh, sixty years ago!)

We feel good about sharing. Well, and we also bake more than we can eat.

Eating a chunk of our bread each day has been something I’ve done for decades—since 1986 when I bought the starter in Skagway, Alaska, and have been using ever since.

But, lately, my appetite’s been changing. I don’t eat nearly as much as I used to. I can’t. I can no longer exercise (dizzy, yes, but I’ve also always needed to watch my weight), and the combination of dizziness and Covid has kept me pretty much indoors. Often I eat no sourdough at all at supper—so without our son and his family I don’t know what I’d do with all the loaves.

Lately, both our grandsons have shown an interest in the dough, so it’s likely I’ll pass it along to them one of these days. Who knows?

I do know this: I always used to look forward to my Sunday baking, but now it’s become more and more of a chore—a chore that usually has a tasteful outcome, sure. But is it a wise use of my effort and time?

Not so sure any longer.

Thursday, September 9, 2021

Here I Come to Save the Day!

Tuesday, September 7, 2021

Grammar and Usage Mavens

I did a FB post the other day about an “error” in grammar I’d stumbled across in an essay by Ann Patchett, a writer whose complete works I’ve just finished reading.

This is the post and the error:

All right, you “whoever-whomever” mavens, how about this one, published in a collection of essays by Ann Patchett:

“I promised whomever was listening that from those very ashes the small independent bookstore would rise again” (This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage, 234).

Some people who commented said that the distinction was one that, in recent years, has been going away, disappearing into the swamp of Distinctions Lost.

I agree.

It seems as if the only time most people use whomever is when they’re trying to sound ... sophisticated. And often they’re just flat wrong (as Patchett was—so unlike her). When you’re using whoever/whomever, you have to determine how it’s being used in its own clause—and ignore the rest of the sentence.

In this case, the W word appears in the clause “W was listening.” So ... it’s the subject of its own clause, and that clause in its entirety, not the W word, is the direct object of the sentence.

This is true even when it looks weird to you: “Give the candy to whoever asks for it.” This is correct for the same reason the earlier one was: It’s the subject of its own clause—and the entire clause is the object of the preposition to.

Here’s a correct whomever: Give the candy to whomever you like. It’s not the to that makes it correct (as we’ve seen), but because the W word is the direct object of its own clause. I always found it useful to substitute he and him for who and whomever. In the example above, the clause becomes Him you like.

You can see why the rule is evanescing: Too much to think about in these days of texting!

Lots of other rules I learned in school have already bid buh-bye and are totally gone—or barely visible far in the distance.

The difference between may and can. The apostrophe. (On social media I see it hanging about, looking for an exit.) The use of the colon, the semicolon. The difference between healthy and healthful. And countless more pairs of words.

You just have to remember: We made up all these rules, and when the rules become irrelevant or arcane (like old English teachers), it’s time to discard them. Or to accept that such discards are going to happen eventually.

Sunday, September 5, 2021

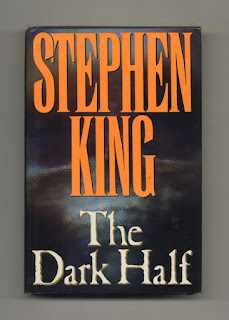

Stephen King Redux

Friday, September 3, 2021

Thomas Berger

I don’t know what got me thinking today about Thomas Berger (1924-2014). Could it be that I’m sitting right across the room from his shelf of books?

Could be.

I first became aware of him when I read Little Big Man, 1964, a novel about Custer’s Last Stand, a novel purportedly told (humorously and movingly) by a very aged man, Jack Crabb, who claims to be the last survivor of that battle, a man who was captured and adopted by a Cheyenne tribe in his early years.

Crabb also meets about every other famous gunfighter who once roamed the West.

Dustin Hoffman starred as Crabb in the very popular 1970 film directed by Arthur Penn. (Link to film trailer.)

Joyce and I were married in late 1969, and it’s one of the first books I told her that she must read. She did—and loved it, too, and taught it in her frosh English course she was teaching up at Kent State as she began her doctoral program there.

I went back and read Berger’s other novels (some dealing with his experiences in WW II), and then on and on until he quit. (And I read Little Big Man several times.)

And one thing I noticed: They were all different—each from the others. He has a King Arthur novel, and he explored about every genre after that, each novel displaying his characteristic wit, each novel making me shake my head in wonder and admiration.

I have a college friend, Bill Heath, who got to know Berger well and did some writing of his own about him. And I think it was Bill who first told me about him. That’s a gift I can’t repay

But the appeal of Little Big Man?

A lot of it has to do with my long fascination with Custer’s Last Stand. Early in my boyhood I read a book about that battle (written by Quentin Reynolds), and I re-read it about a dozen times.

As my life went on, I read scores of Custer books (fiction and non-). I read his own books—and his widow’s. I visited the actual battlefield several times. Bought a Custer Toby jug. Oh, and I took our family a few times down to see New Rumley, Ohio, where he was born and where stands a large statue even now.

Of course, the more I read about him the more I realized he was not always the Good Guy. He did some heinous things to Native Americans.

But he also was a major factor in winning the Civil War battle at Gettysburg.

Still ...

So, my fascination has cooled with Custer.

But not with Thomas Berger, whose work delighted me throughout my middle years. No way to thank him for that.