Tuesday, June 30, 2015

My Bathroom Photographs, 3

A little series about the photographs hanging on the walls in the little half-bath that's near my study.

Okay, in earlier posts I've written about the picture of my great-grandfather Dyer and his family (late 1880s),about the 1959 picture of my two brothers and me in Rugby, ND ("the geographical center of North America"). And now this ...

Again, the Three Dyer Boys are together. At the time (left to right) we were Davi, Danny, and Dickie Dyer. (Maturity--or, rather, additional years--converted our names to Dave/Davis, Dan/Daniel, Richard.) I think I was in junior high when I decided "Danny" would be no more. I started insisting on "Dan"--still my name to most--though I've always published as "Daniel" (sounds more ... what? ... respectable? venerable?). My mom and brothers still use "Danny" now and then--as does Joyce, my wife.

The picture dates from around 1950, I guess (Davi was born in September 1948--he looks kind of two-ish or three-ish, doesn't he?). I turned six in 1950 (late in the year). Dickie turned nine late that year--very late (his birthday is in late December).

I actually remember a few things about that day. We were in a photographer's studio in Enid, Oklahoma, all sitting on a little hassock. It was beige leather (or faux leather?). The photographer told me to straddle it as if I were riding a horse. And that endeared him to me forever, for I was already certain that I was going to be a cowboy. I mean, someone had to take over the protection of the West once the Lone Ranger and the Cisco Kid and Hopalong Cassidy retired, right?

We're all wearing somewhat formal clothing--even little Davi, whose suit coat is buttoned to the top. Our collars are all out (very fashionable!)--no neckties. So it must be summer, when even church--normally a fierce formality in our family--relaxed its dress code a bit in the oppressive Oklahoma heat. My coat is fluffed up a little at the bottom. Needs to be smoothed down. I'm guessing that my mom or grandmother made those jackets for Dickie and me. Both were wonderful at the sewing machine, and among the last manual skills my mother lost was her stitching on the quilts she made for all of us. Davi's is certainly homemade.

Another clue that it's summer? I'm smiling. School's out. If you had told me then that I would become a teacher, would spend my entire adult career in schoolrooms, I would have laughed in your stupid fat face. Go willingly to school? No way! Like Shakespeare's "whining schoolboy," I was the kid "creeping like snail unwillingly to school."

We're all smiling, all showing our teeth, though Dickie has recently lost one. My tongue, for some reason, has decided to come out for some air and lies poised beneath my upper teeth and if I'm about to say "lasso." What's odd to me now? I never show my teeth in posed photographs now. Not sure why. Probably some deep psychological trauma, long unresolved.

Our haircuts are virtually the same--as they would be until adolescence when Teen Angst brought to our mouths some different words to tell the barber. I will not--for the sake of Family Harmony--reveal which one of us no longer has much hair. That would be unkind. Davi was the only blond among us--though we all have blue eyes. Dickie and I had darker hair, though when I was a lad and played outdoors in the summer from dawn to dark, I would sometimes get a little sun-bleached streak in front, a faint streak evident in this school photograph (accidentally torn)--look right next to the part--a little wisp of blond. (Now, of course, it's virtually all white.) (No comments on my taste in attire for a school photo.)

Dickie seems to be looking at the camera; Davi and I are looking more to the left. Is that where Mom is? Surely she was--at the moment--urging us to smile? To show our teeth?

My ears seem a little more ... prominent than those of my brothers. Odd, because I did not listen too well as a kid. (Still don't.)

Our hands are weird. Davi seems uncertain what to do with his. My left hand--a little blurred--seems in motion, perhaps to smack away Dickie's hand, which, oddly, seems to be under my leg. My right hand is probably on the six-shooter I didn't have but wished I did.

So ... three smiling hopeful little boys (who can't wait to get home to change out of those hot church clothes). Two of us our in our seventies, making us some ten years older than our Osborn grandparents were on that day. G. Edwin and Alma Lanterman Osborn lived near us in Enid then. In my view they were ancient. Our parents were also very old. In 1950 my mom turned 31, my dad 37.

Monday, June 29, 2015

More Nonfiction in English Classes?

There was a front-page story the other day (June 20, 2015) in the New York Times. Headline: "'Tom Sawyer' and Court Opinions: A New Mix in English Class" (link to the story). The piece was about the effects of the Common Core on the public school English curriculum: "English class looks a little different," noted the reporter, Kate Taylor.

Yes, the Common Core has issued a "call for students to read more nonfiction," Taylor continued.

All right. Let's flash back a little. When I was in high school (1958-1962), we read precious little nonfiction in English class--if, in fact, we read any at all. All year (when we weren't working on grammar and usage and vocabulary and the like) we read poems, stories, plays, novels (not too many of those, however--though I do have sad memories of Great Expectations, for which I--a ninth grader--was profoundly unready, unwilling, unable, un-everything).

When I began teaching English myself in a public middle school (fall, 1966), I continued doing unto others what had been done unto me (see previous paragraph).

But as the years drifted along, I more and more began supplementing our literary studies with underlying nonfictional factors. When we read The Call of the Wild, for example, we learned about the Klondike Gold Rush. The Diary of Anne Frank, of course, requires knowledge of the Holocaust. And so on.

Even later, teaching at a college-prep boarding school (the final ten years of my career), I liked to teach Henry Louis Gates' fine memoir, Colored People, and I routinely explored with my students the nonfictional terrain of the fictional works we were visiting--from The Crucible to Hamlet to The Awakening to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. And on and on and on.

I spent my vacations traveling around the country touring and photographing sites related to the literature we were reading (I taught American lit + Hamlet, that great American play about that great American hero)--from hometowns to settings to cemeteries.

As we read novels and plays and poems, I customarily gave my students maps and historical and biographical background to help them unlock the texts. It's only common sense, right? How do you read The Scarlet Letter without knowing about Puritan Boston? Or The Great Gatsby without knowing about the Roaring Twenties? Or "The Road Not Taken" without knowing about the forests of New England?

So ... to the extent that the Common Core is urging (requiring?) teachers to do this sort of thing, I am most definitely On Board. Reading a literary text in isolation from its myriads of sources cuts students off from the very humanity of the works they're reading. And English is one of the humanities.

Of course this can be overdone. Fiction is not merely autobiography, cultural history, etc. But those things inform fiction, and the more informed a reader is about them, the better. Doesn't it add a piquant pinch of pepper to Frankenstein to know that Mary Shelley was so stunned by the Mer de Glace in the French alps--the massive glacier (now not so massive, thanks to you-know-what)--that she later used it as the setting for a key encounter between Victor Frankenstein and his creature?

Does it mean anything to you to know that virtually every place name in The Call of the Wild is a location that Jack London had seen during his year in the Klondike (1897-98)?

And so on.

(By the way, I am well aware of the literary theorists who say we should ignore all of this and focus just on the text itself. Doesn't work for me. Obviously.)

Anyway, what worries me about the Common Core requirements is that they will become perfunctory and routine and rote--especially if we test kids on them. What we've learned by all this testing is a simple principle: Whatever is on a standardized test becomes the curriculum. Everything else is superfluous.

But then there's this: I don't agree at all with the notion that kids read too much fiction in English classes. With some rare exceptions, English class is the only time they read novels, short stories, poems, plays. The other seven or so periods a day, students are reading ... nonfiction. Science, history, etc. So I have no problem with setting aside 1/8 of the day for something more imaginary, creative--especially since much of English class has become, due to all the testing, a place for drill and focus on things that are easy to measure.

So ... yes ... urge English teachers to explore with their students the extra-literary worlds of the literature they're reading. But don't mandate yet another series of dry (easily measurable) activities whose sole purpose is to supply "outcomes" to assess on yet another standardized test.

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Sunday Sundries, 57

1. AOTW: A woman is walking her two little white dogs (loosely leashed) across the Hudson Green on the sidewalk; I am approaching her. She is not paying attention (on her cell). As I pass them, one of the little critters leaps at me, tiny fangs flashing. He (She?) misses. Barely. I silently confer the AOTW Award.

2. This week, reading, I came across a locution that was once far more common: normal school. I'm guessing that lots of Younger Folk don't really recognize the term? It was once the name for schools that specialized in preparing teachers (often a two-year program). Here's the origin of the name:

C19: from French École Normale: the first French school so named was

intended as a model for similar institutions

Kent State University, by the way, was once Kent State Normal School.

3. I finished a couple of books this week.

- The Millionaire and the Bard (2015, by Andrea Mays) is the story of the passion for Shakespeare that animated the vast collecting of Henry Clay Folger (1857-1930), a passion that resulted in his accumulation of the greatest collection of Shakespeare-related material in the world, a collection that now resides in the Folger Library (behind the Library of Congress). Although I enjoyed the story of Folger's growing mania, I was struck how the author periodically wrote in support of the Standard Oil Company (Folger was an officer) and even suggested that the anti-trust suit against them was probably not all that good a thing. Anyway, I've been to the Folger several times--used to take Harmon School kids there, too, now and then. Inside, under glass, for the public--a copy of the most expensive book in the world, the First Folio of Shakespeare (the collection of 36 plays, 1623, assembled after his death by his friends and colleagues). Folger owned more of them than anyone else on earth.

- I realized one recent day that I've not ever read much Wallace Stegner (1909-1993), one of the most honored writers in the twentieth century. So ... I acquired a paperback copy of his first book, the novella Remembering Laughter (1937). It blew me away. It takes place on an Iowa farm, where a husband and wife welcome into the family the wife's sister. Things happen. And a psychological iceberg forms in the house. (Don't want to spoil it for anyone who might want to read it.) Anyway, I've started to march through the other Stegner titles I can find. Next up? The Big Rock Candy Mountain (1943).

4. Last week I biked home from Starbucks one afternoon, and, arriving, I found my cell phone was no longer on the clip attached to my belt. Joyce offered to drive over there to see if I'd left it--or if someone had turned it in. Nope. She called, and we decided we'd walk toward each other, following my route. She kept calling my cell as she walked, and when I saw her in the car down near Ravenna Street, I had hopes. And, yes, she'd found it. I'd somehow dropped it near some landscapers. They'd heard it ringing. Kept it until someone showed up to get it. Whew.

5. Some words I thought about this week.

- skedaddle = to retreat, get-the-hell-out The OED is not certain about the origin of this. Some had said that it was Swedish or Danish, but ... nope. Perhaps English or Scottish dialect? No one's sure.

- savvy = n. common sense; shrewdness; practical intelligence; v. to know or understand something Probably from pidgin and creole versions of English.

6. I bought a bottle of One-a-Day vitamins the other day. Opened it. Saw that, as usual, it was not even half-full. What is up with that? Do they use bigger containers to make us think we're getting more?

Saturday, June 27, 2015

My Bathroom Photographs, 2

Number two in a series about the photographs hanging in the little half-bath that adjoins my study.

This picture, which hangs right above the one of my great-grandfather and his family (see earlier post), comes from the summer of 1959. Little brother Davi (on the left) was 10; I, 14; older brother Richard, 17. He had just graduated from Hiram High School and in a few weeks would commence his career at Hiram College. This was in the days before selfies, so I'm guessing Dad took it--though Mom could have, as well.

We are on our way to Oregon for a family reunion (Dad's family). and we have stopped in Rugby, ND, which, Mom has informed us from information she's obtained in one of the little AAA travel guides we always travel with, is the geographical center of North America.

We have been traveling across the northern plains on US 2, a gorgeous road that, years later, I will take with Joyce and our son, Steve, on yet another trip west for yet another family reunion. We will stop at Rugby, too ... but let me delay that part of the story.

Davi is wearing a shirt similar to shirts that both Richard and I had. We called them our "coronation shirts" because our grandmother Osborn had made them from material she bought in England when she and my grandfather were there for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on June 2, 1953. I see on the Internet that it was a rainy day for the royal procession, and I picture my grandparents under an umbrella, waiting for a glimpse of the young queen (she was 27).

Around Davi's neck, his Kodak Brownie camera.

I've had a recent haircut, it seems. I wore my hair short throughout my public school days--and on into college. My shirt's untucked. Rowdy kid. About to be a sophomore at Hiram High.

Brother Richard does not look happy. I don't think he wanted to go on this trip.

But there he is--and there we are at the Geographical Center of North America.

Or were we?

On Rugby's website (which I just now consulted for the first time) I see that the Center is not exactly where the marker is. (Link to the site.) I wondered why I felt so ... uncentered ... throughout high school!

Okay, so ... years later. Joyce, Steve (elementary school age), and I stopped in Rugby. I wanted another picture. I set up our camera on the tripod. Took a few shots using the camera's timing feature.

But this, of course, was in the Old Days--before instant feedback on your photos. I had to wait until I got back to Ohio; I had to wait until I sent the film off to be processed; I had to wait for the pictures to come back.

And when they did?

Well, now I need to explain something else: This was an old-fashioned camera that required you to open the back of the camera, hand-load the film, wind it around the spool, close camera, take pictures.

But when our shots came back ... well, I saw something very odd. The shots at Rugby were double-exposed. Superimposed on Joyce, Steve, and me was an image of my uncle John Dyer and his family sitting around a picnic table.

I'd inadvertently used the film twice. All shots similarly ruined. In a fit of self-loathing, I threw the prints away.

And now, of course, I'd give all to have them back.

|

| Internet photo. |

Friday, June 26, 2015

Frankenstein Sundae, 137

So … in 1894, Mark Twain, enraged about the

mistreatment of Harriet Shelley by a Bysshe Shelley biographer,

rose—fiercely—to her defense. In some ways, Twain was past the prime of his

career (Huck Finn had appeared about

ten years earlier), but his bitterness about the “damned human race” would only

increase as he aged. Human ignorance terrified Twain, and he wrote about it

over and over—from his earliest books onward. He knew that our ignorance—in

some cases our willing, even eager, ignorance—could (and probably

would) doom our democracy. In 1905 he would write an essay called “On the

Damned Human Race.” In it, he sardonically compares us to the “lower” animals …

and finds us wanting.

Throughout these recent pages I have sometimes referred

to “poor Harriet.” So perhaps it’s time to write a little about her final days,

which must have been hellish. Remember, in August 1811, he’d swept the young

Harriet Westbrook, who just a few weeks earlier had turned 16, away from her

family, had taken her to Scotland, where marriage laws were more relaxed.

Then he yanked her around—Ireland, Wales—“educating”

her along the way, trying to craft her into both a wife and a Shelleyian

disciple, risking her life (the shooting in Wales), and, soon, drawing other

women into his alluring orbit.

In the summer of 1814—he’d not been married to Harriet

for three years—Bysshe ran off with two more teenage girls, Mary Godwin and Claire

Clairmont, returned six weeks later in disgrace to London, where he visited the

Westbrooks (Harriet had returned to her family) and tried to persuade her to

join his little commune. She declined.

Oh, and at the time, Harriet was already the mother of

a daughter, little Ianthe (born in June 1813), and was pregnant with Charles,

born about two and a half months after her wayward husband returned from his

dash to the continent with Mary and Claire.

Does it take much to imagine Harriet’s despair? She

was not yet twenty, and her life was ruined. With her shattered reputation, no

other man would rescue her. Her family members were scandalized. Having her in

the house was an embarrassment.

By September 1814, she’d moved out of her family home,

had found, with their help, an apartment, had begun going by the name of “Mrs.

Smith.” Money was not a problem: Bysshe had promised her an allowance; her

parents helped, too. But her depression was deep. And would only deepen.

And a couple of months later she left the place. And

vanished.

A month after her departure—on December 10, 1814—her

body was found floating in a river.

Thursday, June 25, 2015

My Bathroom Photographs, 1

Near my study is a tiny half-bath (why call it that when there's no bath at all!?!?): toilet, sink. On the walls I have put some pictures of various sorts--and, now and then, I think I'll show you one and write about it a little bit. (As close as I usually get to bathroom humor.)

The first--just inside the door, left side--is a photo I think I've posted here before. Tough. Look at it again at the top of the page.

It's a picture I got from my dad--and copied--and enlarged--and framed. It's circa 1887 in Centerville, WV (see red flag on map).

It shows my great-grandfather Addison Clark Dyer (bearded--like all other handsome Dyers) with his family. My grandfather Charles Morgan Dyer (whom I never met--he died long before I was born) is at the far right in the picture, just to A. C. Dyer's left. I don't know the names of all my great aunts and uncles. On the back of the photograph is this: Minnie is his wife; then Charles Morgan, Mary, Laura, Harry ... and I'm not at all sure who is who.

A. C. Dyer had been sheriff of Braxton County, WV. From what I can gather from an old history of the county, he was the sixth sheriff, following George H. Morrison, James W. Morrison, Henry Bender, Able M. Lough, and John Byrne. (Here's a link to an online copy of the history.) The Dyers had a long history in Va. and W. Va., a history I'll not get into now, but, oddly, my mother was born in Martinsburg, WV, in 1919 but has no memories of the place. Her family moved away when she was tiny. Years later, Joyce and I went there and took a bunch of pictures and gave them to Mom, who was ... unmoved, let's say.

I've always been interested in family history, but A. C. Dyer's story grabbed me especially in the early 1980s when, after a four-year absence that saw me on the faculties of Lake Forest College and Western Reserve Academy, I returned to teaching at Harmon School in Aurora. In my absence the school had adopted a new anthology, Exploring Literature (Ginn & Co.), which included Jack London's The Call of the Wild.

I had never read Wild (just in Classics Illustrated form when I was a kid), didn't know anything about Alaska, the Yukon, the Klondike (they were all cold--that I knew), and I didn't know Jack about London. But I got interested (to say the least) and began what would become a ten-year obsession with the novel, the settings, the author.

Early on, my dad told me that A. C. Dyer had gone on the Klondike Gold Rush--and had kept a diary, still in the family. (That diary now sits on my shelf; I will soon pass it on to our son.) Dad--as part of a sabbatical project--had transcribed that diary, and he sent me a copy. Which I devoured. A. C. had gone there later than London himself, who'd zoomed up there almost as soon as the news of a strike arrived in the summer 1897. But their tenures did overlap a bit; I prefer to think that they met and shared a few. And maybe A. C. gave him an idea for a story about a dog--a stolen dog ... Yes, I'm sure that's what happened.

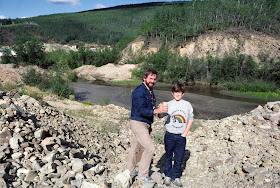

Anyway, in the summer of 1986, our son (who had just turned 14) and I flew to Skagway, Alaska, rented a car, and drove to Dawson City, Yukon, following the route described by my great-grandfather. We actually found the site of his old gold claim (still active, now posted with dire (!) threats about trespassing); we photographed the site, grabbed a rock from the tailing piles, and skedaddled.

I'd show you the rock--but we gave it to our son not too long ago. But here we are, holding the rock, standing at the site. A selfie the old-fashioned way: tripod and timer.

Wednesday, June 24, 2015

Frankenstein Sundae, 136

Twain's essay defending poor Harriet Westbrook Shelley was in a set of Twain's works one of my grandfathers had owned.

I’m not sure why G. Edwin Osborn bought those books.

My uncle Ronald (G. Edwin’s son) once told me that he’d bought them from a

traveling salesman and that he (Ronald) could remember hearing my grandfather

laughing from his bedroom late in the night.

When my grandmother died in 1978 (he had died in

1965), the books—little green volumes,

each slightly larger than the average

mass-market paperback today—came to me, and they sat proudly on our shelves

until a few years ago when I gave them to our son. I used those volumes often

and read some of the lesser-known works that the set included—like his long

essay defending poor Harriet Westbrook Shelley.

I “read” my first Twain in fourth grade. I placed read in quotation marks because I

actually listened to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which my

wonderful fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Stella Rockwell (Adams Elementary School;

Enid, Oklahoma), read aloud to us every day after recess—if we were “good,” that is. Mrs. Rockwell had asked our class to

bring in books for her to read, and we owned a little pair of books—Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—that had been published together.

One was red (Tom?), the other green. I brought in Tom; she agreed to read it.

When we finished Tom

Sawyer, I swiftly brought in Huck

Finn, which she also read to us—and which I adored. Years later, of course,

reading it on my own, I discovered that careful Mrs. Rockwell had bowdlerized

the text for her nine-year-old students. No nigger

(even in racially segregated Enid in the early 1950s, Mrs. Rockwell tolerated no racism in her

class), reduced brutality (I was horrified, later, at the scene when Pap Finn,

supremely drunk, chases Huck around the cabin trying to kill his own son), and

so on—but I remember most of all that voice,

the voice of Huck Finn that, as Hemingway later commented, changed American

literature. The voice that I first heard in the soft Oklahoma drawl of one of

the best teachers I ever had, kindergarten through graduate school.

Later, a teacher myself, I used Twain now and then

with my middle school students, but it wasn’t until near the end of my career—when

I began teaching high school juniors at Western Reserve Academy—that I became a

certifiable Twain freak. I taught Huck

Finn every spring my final ten years, and throughout those years I was

visiting and photographing all the Twain sites I could, reading all the biographies

of him, reading his complete works—which takes some doing.

I had actually been to Hannibal, Missouri (his boyhood home), many

years earlier: My wife and I—on our honeymoon—stopped there on our way home from

New Orleans. Christmas time. 1969. Not much was open, but we saw some of the

sites. The house. And, especially, the Mississippi River, still flowing by,

dominating all.

I went back to Hannibal any number of times, too. One

of my favorite visits was in July 2004—to the Mark Twain Cave, setting for those creepy scenes with Tom and Becky and the murderous Injun Joe, the scenes that frightened me beyond words (with

words) back in the 1953-1954 school year when I sat, sweating from a fierce

recess, trying passionately to be “good” so that Mrs. Rockwell would read to

us, then, when she began, being absolutely transfixed by the adventures of that

clever boy from that little river town, that clever boy whose even more

interesting friend, Huck Finn, would in some fundamental ways change my life.

I went back to Hannibal any number of times, too. One

of my favorite visits was in July 2004—to the Mark Twain Cave, setting for those creepy scenes with Tom and Becky and the murderous Injun Joe, the scenes that frightened me beyond words (with

words) back in the 1953-1954 school year when I sat, sweating from a fierce

recess, trying passionately to be “good” so that Mrs. Rockwell would read to

us, then, when she began, being absolutely transfixed by the adventures of that

clever boy from that little river town, that clever boy whose even more

interesting friend, Huck Finn, would in some fundamental ways change my life.Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Back to Seidman Cancer Center

|

| Seidman Cancer Center University Hospitals Beachwood, OH |

I

got a scare last week. On Wednesday I had my quarterly blood test to check the

level of my PSA (Prostate Specific Antigen), a number which should be

undetectable because of the surgery to

remove my cancerous prostate gland almost exactly ten years ago (June 9, 2005)

at the Cleveland Clinic.

But

that surgery, which we all hoped would terminate the cancer—remove it!—instead commenced a decade of

procedures and tests and trips to clinics and worries and diminishments of the

life I'd known.

As

followers of these posts know, the cancer returned to such a level that I

underwent seven weeks of daily radiation treatments down at the Clinic in 2009.

And

things calmed for a bit.

Then,

about two and half years ago, my PSA started rising again, and by July 2013 my oncologist

at University Hospitals (I'd switched from the Clinic) told me it was time for

hormone-deprivation therapy. Quarterly injections of Lupron, a drug that zaps

testosterone, the “food” of prostate cancer.

With

the usual consequences. Significant loss of energy. Emotional fragility. Depression. Weight

gain and redistribution. Hourly sweating—sometimes in drenching fashion. Loss of libido.

But

it worked. In just three months my PSA dropped from 22.9 to nearly zero, where

it has stayed for two full years, a situation that has surprised my oncologist

because the intensity of my cancer was a Gleason 9 (there ain't a number much

worse on this scale that runs from 2 to 10).

In

any case, Lupron is not a cure. It

temporarily blocks the cancer cells, but inevitably they figure out a

workaround; then other therapies and drugs commence. But nothing will cure me.

I'm hoping to hang on until researchers make that great breakthrough.

Anyway

… last Wednesday was my quarterly PSA test. I was a tiny bit hopeful. Although

I know that at some point my score

will begin to rise again, I was grasping at a flimsy straw my oncologist had

offered me back in March: If I stay “undetectable,” well, maybe we can go off Lupron for some months. Maybe—one

last time—I'll get to be Who I Was.

I

waited a day after the test, then emailed my oncologist about the result. It

came back almost immediately (he's wonderful about that—and about so many other

things).

And

I was shocked. Here's what it said: <.10.

I was detectable.

I had a weekend full of worry.

Then

yesterday morning at our appointment at Seidman Cancer Center he reminded me

that <.10 is undetectable. The

number is just the cutoff line. At .10 I have a reading; at less than .10 I do not.

My

relief was more than palpable; it was alpine.

And then my oncologist reminded me of my choice--off Lupron for a while?

Joyce and I were both torn. Lupron has been working--though, of course, it will not work much longer. Two years out--especially for someone with a Gleason 9--is a long, long time. (He'd originally told me it might be effective for only six months or so.)

But what if ...? What if there's a chance I could be Me again? Even if just for a while?

Before I left the office, I told him: "Let's go off it."

He agreed--though I will be getting PSA tests every month now instead of quarterly. Which, of course, heightens the anxiety by making it more frequent.

But on the way home--and throughout the rest of the day and evening--Joyce and I have continued to discuss the pros and cons. I vacillate like a politician uncertain of his audience. Yes. No. Yes. No.

Fear struggles with Hope.

Monday, June 22, 2015

Evening Drives, 2

A day or so ago, thinking about Father's Day--about my father--I posted here a piece about the "evening drives" my mom and dad, back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, liked to take up to Burton, Ohio, just about a dozen miles due north of our home in Hiram, Ohio, where Dad was teaching at Hiram College (1956-1966). As I wrote there, they liked to get a maple soft ice-cream cone up there at the little stand on the town square. They like to take their young sons along, Their young sons liked it ... mostly.

Then, Saturday afternoon, I spoke with my mom (95) on the phone, reminding her of those drives, and she very well remembered the ice cream. I told her I wished I could send her a cone but that it would be maple milk by the time it got to her. She replied, "Not the best way to eat it." True, Mom. Very true.

After supper on Saturday, Joyce and I decided to drive up to Burton ourselves, just to see--and, hey, if ice cream was in our future (maple ice cream!), well, you can't really help that, can you?

We drove over to Hiram first, then down Hiram's north hill on Ohio 700, past our old home (11917 Garfield Road), and on up to Burton, just the way we had always gone a half-century ago.

So much has not changed. Farms. Amish buggies. Orange day lilies lining each side of the road. Sure, there are some newer places, some buildings that are gone. But my 1959 self would have known where he was--without question.

As we pulled into Burton and saw the village green, I noticed immediately that the ice-cream stand was gone. Remaining was the old cabin that had been on the site since 1931 (I just learned on the Internet--link to information about it). And I could tell that Burton has decided to keep the green as rustic as possible--a decision that, of course, means "no ice-cream stands." But Joyce took a picture of me standing (near?) where it used to be.

We drove on into the little village, which looks much as I remember it: an American Small Town, unsullied by big-box stores and other suburban and urban clutter. We found an ice-cream shop (closed) but then noticed an appealing little coffee shop across from the green. Outside were some older men (my age?). I stopped and asked if any had lived there a long time. A couple had. "Do you remember the ice-cream stand on the green?" One guy did, said it was removed in the 1960s. (I would guess late 1960s?)

And then ... something weird. I had been feeling weepy the whole time--remembering our family, our drives, my dad. And echoing around in my mind was that old Dylan song "I Shall Be Released." I often heard it in the Open Door Coffee Co. in Hudson (my morning hangout), and although it's a song about a guy in the slammer, it's also, of course, about ... Life. And Death. (Link to YouTube performance by Dylan, The Band, and others.) Something about that song wrings tears from me.

Anyway, last night we asked the Old Guys Outside the Coffee Shop if they sold ice cream inside. And got the affirmative answer we craved. Inside, we saw that maple was not one of the flavors, so I settled for a decaf to sip on the way home.

Near the inside entrance, two other Old Guys had set up to sing and play--a guitar, a five-string banjo. As we were about to head out the door, they launched into ... "I Shall Be Released."

I stopped. Leaned on a post. Listened till they were finished. Told them I loved that song.

We headed out to the car, and on our drive home--all the way--I wept like a child who has just lost his parents.

**

* This morning (Sunday) Joyce and I, as usual, walked over to Open Door for a little breakfast, coffee (tea for Joyce), the New York Times, and talk.

As we were readying to leave ... on the music system ... guess what was playing?

** At our Father's Day picnic at our son's house down in Green, Ohio, I got a surprise. My cell rang. Caller ID said it was my mom. Mom never calls me--she hasn't been able to dial out for a few years. Usually, when I see her ID, I know that one of my brothers is in her assisted living place, making the call.

But not this time. She wished me a Happy Father's Day, talked to our son and wished him one as well. Talked with Joyce and our daughter-in-law, Melissa. And one of her great-grandsons, Carson (6). Carson told her he loved her. I almost lost it.

I told her we'd driven to Burton the night before. Her reply? "Ohhhhhhhh" in her soft wistful voice, the one that communicated a simple message: I want some maple ice cream. Hearing the ice-cream stand was gone, she sighed again.

Then we lost our connection; I called right back. One of the aides in the unit answered. She had placed the call for Mom, and I was so overwhelmed with gratitude for that thoughtful act that the tears started again.

A weepy couple of days for me ...

Sunday, June 21, 2015

Sunday Sundries, 56

1. AOTW: No real candidates this week--the usual doofuses in traffic, that's about it. So--impossible as it may be to believe--no award this week!

2. Reading something the other day, I came across an allusion to the game of Post Office. It's time to confess: Although my friends and I talked about this game in junior high (okay, and later, too), I never actually played the game; in fact, I didn't even know what the "rules" are. Enter Wikipedia:

The group playing is divided into two groups – typically a girl group

and a boy group. One group goes into another room, such as a bedroom, which is

called "the post office". To play, each person from the other group

individually visits "the post office". Once there, they get a kiss

from everyone in the room. They then return to the original room.

Once everyone in the first group has taken a turn, the other group

begins sending members to the first room.

Probably the raciest game I played back then was Truth of Dare, a game I liked because you could lie and be a chicken.

3. I was thinking the other day about the changes in coffee. Throughout most of my life, when you went to a restaurant or a coffee shop, you ordered ... coffee. The only variation was decaf. Now ... light, bold, medium, dark, spicy, etc. And, of course, instead of five cents, it's now two dollars (or more).

|

| issue from back in the day |

|

| issue I found in the waiting room |

5. The other night--while Joyce was off somewhere--I watched, via Netflix, the DVD of Foxcatcher, a 2014 film I'd read a lot about but did not ever go to see when it was in the theaters--which, if I remember correctly, was not all that long a time, at least around here. (It got five Academy Award nominations--no wins.) Based on a true story of a murder executed in January 1996 by John Du Pont (yes, those Du Ponts, the fabulously wealthy ones). Du Pont, a devoted (mad?) fan of amateur wrestling, had gathered at his estate some of the best wrestlers in the world (including characters played by Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo; the later is the one whom Du Pont kills). His estate--called Foxcatcher--was where he set up a training site for the world championships and Olympics. Things get freaky before the gunfire, but the performances were excellent, top to bottom, including a very off-type Steve Carrell, who played Du Pont. Not a pleasant film to watch--but a powerful one. (Du Pont died in prison in 2010.)

5. The other night--while Joyce was off somewhere--I watched, via Netflix, the DVD of Foxcatcher, a 2014 film I'd read a lot about but did not ever go to see when it was in the theaters--which, if I remember correctly, was not all that long a time, at least around here. (It got five Academy Award nominations--no wins.) Based on a true story of a murder executed in January 1996 by John Du Pont (yes, those Du Ponts, the fabulously wealthy ones). Du Pont, a devoted (mad?) fan of amateur wrestling, had gathered at his estate some of the best wrestlers in the world (including characters played by Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo; the later is the one whom Du Pont kills). His estate--called Foxcatcher--was where he set up a training site for the world championships and Olympics. Things get freaky before the gunfire, but the performances were excellent, top to bottom, including a very off-type Steve Carrell, who played Du Pont. Not a pleasant film to watch--but a powerful one. (Du Pont died in prison in 2010.) 6. This week I finished reading the "lost" 1953 pulp novel by Gore Vidal (writing as "Cameron Kaye"), Thieves Fall Out. Reissued just this year, Thieves takes place in post-WW II Egypt and tells the story of an American, Peter Wells, a resourceful young man, a war vet with some skills (think: Liam Neeson in the Taken films ... well, Wells is not that skilled) who gets swept up in a plot to steal, smuggle, and sell a priceless necklace from Back in the Day (which, in Egypt's case, was a long, long, long time ago).

6. This week I finished reading the "lost" 1953 pulp novel by Gore Vidal (writing as "Cameron Kaye"), Thieves Fall Out. Reissued just this year, Thieves takes place in post-WW II Egypt and tells the story of an American, Peter Wells, a resourceful young man, a war vet with some skills (think: Liam Neeson in the Taken films ... well, Wells is not that skilled) who gets swept up in a plot to steal, smuggle, and sell a priceless necklace from Back in the Day (which, in Egypt's case, was a long, long, long time ago).Double-crosses, 1950s sex scenes, fisticuffs, gunfire, ex-Nazis--all come into play in this romp through the hard-core crime genre.

Vidal's characteristic slicing wit is not heavily present here, but there are glimpses behind the conventional structure and prose of the literary talent who would write so many great essays and plays (Visit to a Small Planet), entertaining novels (Lincoln, Burr, etc.). One chapter ends with this: "In the hills across the river a jackal laughed" (101). Now that's Gore Vidal.

Percolating underneath the novel is a rebellion against Egypt's King Farouk, who ruled from 1936-1952. The revolution that erupts at the end of this novel is the one that deposed him in 1952 (he fled to Italy after Nasser's forces overwhelmed him and died in Rome in 1965).

Farouk, a handsome young king, became rather ... portly ... later on and was the subject of jokes (one character in Vidal's novel calls him "Fat Boy" (220)), one of which, a drawing I remember from boyhood, was the first cartoon I didn't understand. Dad had to explain it to me. See below:

Shown this drawing, you were supposed to say what it is. Answer: King Farouk on a bar stool.

Well, at the time, I didn't know who King Farouk was, and I certainly didn't know anything about his weight.

I found this image on the Internet, but my memory is that the drawing I saw was far more exaggerated in ways you can imagine.

Saturday, June 20, 2015

Evening Drives

Thinking more and more about my dad ...

When we were living in Hiram (Aug 1956-Aug 1966), my dad reached his fifties. It doesn't seem like much of an age these days (when 50 is the new 15), but he had outlived his own father, who had died when Dad was a teen, and, of course, Dad had seen Death in all its horrible guises during World War II. I began back in Hiram--though I could never have articulated it--to realize that Dad was feeling older. And definitely mortal. (He'd already had kidney stone surgery on both kidneys--back in the day when the surgeons cut you from bellybutton to spine: He had a circle of scars around his middle.)

I watched Dad slow down, watched him start taking it easy. TV. Naps in his chair ("Just resting my eyes," he'd say). Less physical exercise--not that "working out" was something that men in his generation did. He looked at me kind of cockeyed when I began jogging in the late 1970s, sometimes 8-10 miles a day, but usually 4-6. When we'd visit them in retirement out in Cannon Beach, Ore., I'd go run on the beach, and while I was gone, Dad would rest his eyes.

After some mini-strokes slowed him down even more, Dad would go to water therapy in the morning--eagerly so. My mom told me it was because he liked to look at the women. I'm guessing they didn't mind looking at him, either.

Anyway ... back in Hiram. One of the manifestations of his new--what?--tranquility was his fondness for taking evening drives with my mom. And because they both loved what they called "soft ice cream," these drives frequently terminated at a frozen custard stand, often up in Burton, where my folks could get maple cones. Which they adored. Younger brother Dave and I often went along. (Where There Is Ice Cream, Kids Will Go.)

But the desultory, soft-shoed driving of my dad drove me crazy. I was in high school. Getting my own license. Riding around with friends who, unlike Dad, saw the pleasures in speed. Dad would creep up to Burton, just about 12 miles due north of Hiram on Ohio 700 with a little jog to the left on Ohio 168.

Dad seemed to see some virtue in 25 mph. Dave and I (and even Mom) would sometimes complain about his testudineal (like a tortoise--I love it!) progress, but Dad would take a puff on his pipe and wax eloquent about the farmland, the evening sky, any wildlife we happened to see, the family fellowship--all the other things that annoyed the hell out of me as a Snotty Adolescent. I wanted ice cream! Not yet another tour of northern Portage and southern Geauga counties.

I'm seventy now. Nearly twenty years older than Dad was when we went on those dawdling drives up to Burton.

And now Joyce and I, after supper, often take a testudineal drive over to Aurora (via the back country roads) or to Kent (ditto), admiring the farmland, the evening sky, any wildlife we happen to see. Our family.

I'll end with this: Dad earned some slow evening drives in his later years. Grew up on a farm. Depression. World War II. Korea. Three (sometimes snotty) sons. He taught the regular academic year. He taught in summer school. An ordained minister, he filled in at various pulpits around the area on Sundays. He stayed in the Air Force Reserves and retired a Lt. Colonel. My life, by comparison, looks, well, uncomplicated.

I of course regret the grousing I did as we drove north those Hiram summer evenings more than a half-century ago. And I would like one more drive with Dad so that I could tell him so. He would smile. Puff on his pipe. Cut his speed to 23. And ask me if I noticed that hawk on the telephone line.

Friday, June 19, 2015

Frankenstein Sundae, 135

Entering the debate about Bysshe Shelley's behavior ... Mark Twain!

Janet Todd, a scholar sensitive to the explosive

climate in the Godwin household, is not easy on William Godwin during this

period. Mary’s father, she wrote, “made things worse by imposing his own

attitudes on the household.”[1] I guess. And, we must remember, 1814 was

not a time when women—daughters, wives—dared confront men too directly, for

men, well, ruled. Women were barely a

step away from property, despite the philosophies of remarkable women like Mary

Wollstonecraft, who, if she could have returned from her grave for a view of

the Godwin household at this time, would have no doubt shaken her weary head in

disbelief and had some harsh words for her one-time husband, who’d so quickly

altered, if not entirely abandoned, his radical philosophy when someone in his

own household actually employed it in her life.

Meanwhile, Todd will not let our attention drift away

from the women whose lives the various men were tormenting with their behavior.

Mary Jane Godwin—as unpleasant a person as she may have been—had to watch

helplessly as Bysshe Shelley seduced her daughter (there’s no other locution for

it, really) away from the family.

And Harriet Shelley, Bysshe’s lawful wife. Not quite

nineteen years old when the elopement occurred. Mother of a one-year-old

daughter, Ianthe. Pregnant with a son, Charles (who would be born on November

30, only two months after her wayward husband returned from his six-week frolic

in Europe with two other teenage girls). Bysshe had actually invited Harriet to

join his little harem-in-progress.

She declined.

Mark Twain, by the way, was one of the few writers I

read early in my research who blasted

Bysshe for his cavalier behavior—and who took Harriet’s side, and fiercely so. In

his three-part essay “In Defense of Harriet Shelley” (1894—serialized the three

installments in The North American Review),

Twain was responding to the 1886 publication of Edward Dowden’s The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Shelley, wrote Twain, “has done something which in the

case of other men is called a grave crime …,” a crime that Dowden (in Twain’s

view), well, whitewashed.[2]

In his one-volume version of his Shelley biography

(1896), Dowden had written, “Yet evidence exists which makes one hesitate

before asserting that Harriet had not, at least through indiscretions, if not

through graver error, given occasion for her husband’s belief that she was

untrue to him.”[3]

Twain was outraged by this sort of thing. Here’s some

of what he wrote about Harriet:

“Her very defenselessness should have been her

protection. The fact that all letters to her or about her, with almost every

scrap of her own writing, had been diligently mislaid, leaving her case

destitute of a voice, while every pen-stroke which could help her husband’s

side had been as diligently preserved, should have excused her from being

brought to trial [metaphorically]. Her witnesses have all disappeared, yet we

see her summoned in her grave-clothes to plead for the life of her character,

without the help of an advocate, before a disqualified judge and a packed jury.”[4]

I was affected in another way, working on Twain’s

defense of Harriet. I found his essay in volume twenty-two of The Writings of Mark Twain, a

twenty-five-volume set that I’d inherited from my grandfather Osborn. And that’s

a story, too …

Thursday, June 18, 2015

Missing Dad ...

|

| Dad and his boys, Summer 1956 Enid, Okla. |

Back in June 2008, I wrote a piece about Dad, a piece I'd hoped that the Plain Dealer would publish--but they didn't. And it's been sitting on my hard drive ever since. Waiting.

I've not updated the piece, but it was almost exactly eight years ago, and we all can do arithmetic, right? I do have two grandsons now, not just the one I mention in the piece. And, of course, all Border's stores are gone.

Anyway, here it is, otherwise unaltered from 2008 ...

Father’s Day 2008

I’m standing near the entrance of a

Border's. Arrayed in front of me, occupying an entire display table, are books

for dads. Gifts for Dad, really. For Father’s Day 2008.

My eyes move along the display.

Titles about war. About golf and grilling outdoors. About beer. An employee has

added a few thrillers, too. Stephen King is there, as are a couple of other writers

I’ve never heard of but whose books feature garish jackets, loud titles,

encomiums from other writers I’ve never heard of. The plots of the books seem

as violent as the covers. The sight depresses me.

Is this what a father is? A man who

likes to read about war and booze and golf and serial killers and techniques to

keep that flank steak tender on the grill?

I think of my own father. Born in

1913, he remembered the men coming home from World War I—some limping, some

being led by others. He remembered, as well, the ones who did not come home. Dad, one of 10 siblings, grew up on an Oregon hardscrabble

farm, endured the Great Depression, served as a chaplain in both the Pacific

and European theaters in World War II, was called back to active duty for Korea.

Along the way, he graduated from college, married a remarkable woman, earned a

Ph.D., taught in colleges and universities, sired three sons, ate lots of berry

pie, watched too many football games on TV, laughed raucously, enjoyed himself

tremendously.

He had some dark years at the end. Strokes

and heart attacks felled him. He made the sad declension from cane to walker to

wheelchair to bed. His mind, once a great sun, slowly dimmed, then darkened. It

took years, decades really. My mother had a lot of hard, largely lonely and thankless

work to do.

Is my father somewhere on that

display table at Border's? In a very superficial way he is. He liked golf but

was never very good at it. He used a 4-wood on all par 3 holes. He loved to

grill outdoors, and among my most prized possessions is some Super 8 footage I

shot 40 years ago showing Dad doing his magic with some ground chuck. His last

sentient years he liked thrillers and adventure stories. He turned every page

of every Aubrey/Maturin novel by Patrick O’Brian. By then, I was not sure he

was really reading, but he still felt as if he ought to. When we’d ask him what

he thought of what he was reading, he’d invariably reply, “A great yarn!”

And of course there’s warfare.

He hated it. Would not ever talk about

it. I discovered in my adolescence, quite by accident, that he’d won a Bronze

Star in Germany. And here’s something that stunned me when I was a little boy and

loved little more than reading books about military adventures, books I checked

out every week from our little Carnegie Library in Enid, Okla.

One day I asked Dad, who was reading

the newspaper in the living room: “Did you ever shoot at anyone in the War?”

He looked up at me from his paper,

decided for some reason to answer. “Yes.”

“Did you kill anyone?” I gushed. I

was picturing Davy Crockett on the ramparts of the Alamo. Picturing my dad

alongside, knowing that if he’d been there, the Alamo never would have fallen. Not

in a gazillion years.

He looked at me again. “Kill

anyone? I hope not,” he said. And

returned to his reading.

He

hoped not! What kind of answer was that?

I didn’t understand it then. It took years, really. Probably the answer arrived

in 1972 when our own son was born, when I realized what a horror it would be to

have someone shoot at him. To have him shoot back at someone else’s son.

A few years ago, going through Dad’s

things, I came across a cache of letters. All were to my mother in 1945. From

Europe, he’d written to her just about every day. Some days he didn’t write a

lot. But usually something. He was eager for the war to end. He’d seen enough. He

wrote a horrible letter about feral orphan children scavenging in the ruins of

buildings.

Most of all, he was full of longing

for home. He missed my older brother, age 4. He’d not yet even seen me (I was

born late in 1944). He wrote the word “love” in his letters, over and over and

over again.

I’ve been a father now for more than

35 years. A grandfather, too, for more than three. For 55 years I had a dad. But

on June 15, 2008, I will have lived more than 3500 days without him. It’s a

thought that brings me close to despair.

Until I remember this: Dad knew that

fatherhood was a word that had little

to do with how many burgers he grilled, how many medals or degrees he earned or

putts he sank. Fatherhood means teaching

your children—no, showing your

children—that for the rest of your life, every time you think of your family,

of your home, you want to write the word “love,” over and over and over again.

Wednesday, June 17, 2015

Frankenstein Sundae, 134

The lovers--Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley--return from their elopement--to find ...

In late September 1814, when the impecunious

lovers—Bysshe and Mary, in company with Claire Clairmont—returned to London some

six weeks after their European elopement, Mary was devastated to learn that her

father refused all communication with her. And, in fact, William Godwin would

not speak with her again until the very end of 1816—more than two years after her

return to England—until, because of the suicide of Bysshe’s first wife,

Harriet, Mary and Bysshe married. Now they were “legal”; now Godwin would speak

with his aching daughter who—without her father’s comfort—had suffered the loss

of an infant, had delivered a healthy son, whom she’d named William in the

hope, surely, that this might mollify her father.

But Godwin—as

you may have inferred from these pages—was something of an Odd Duck. Although

Mary Wollstonecraft’s love altered and maybe even softened him somewhat (shall

we resist an ugly-duckling-into-swan analogy? Nah!), when she died in September

1797, he quickly slid back into his curmudgeonly persona. He proved a major

disappointment to Bysshe, who had idolized him, who had considered him a mentor.

Bysshe had read Godwin’s treatise Enquiry

Concerning Political Justice (1793—revised in 1796 and 1798), had read what

disdainful Godwin had written about marriage in that massive volume:

• The method is

for a thoughtless and romantic youth of each sex to come together to see each

other, for a few times under circumstances full of delusion, and then to vow

eternal attachment. [1]

• And how about this beauty? So long as I seek, by despotic and artificial means, to maintain my

possession of a woman, I am guilty of the most odious selfishness.[2]

• Or this? Certainly

no ties ought to be imposed upon either party, preventing them from quitting

the attachment, whenever their judgement directs them to quit it.[3]

Bysshe found in these words, of course, some of the

justification for abandoning his wife, for swooping up teenagers Mary Godwin

and Claire Clairmont and whisking them off to Europe. He had previously told Godwin that, despite being married

to Harriet, he was in love with Mary and wanted to be with her. He—naively,

perhaps—thought Godwin, author of Political

Justice, would go for it.

Nope.

Godwin was horrified at the prospect. Funny how theories

of interpersonal behavior alter when they collide with our own families. He

told Bysshe to stay away. Which, of

course, he didn’t.

Anyway, after the elopement Godwin refused any direct

communication with Mary—but he did

stay in touch with Bysshe, whose money Godwin desperately wanted and needed.

And poor Fanny Wollstonecraft? She was in a horrible

position, having to side (at least feigning to do so) with the adults in the

house—but also very much wanting to see the Tarnished Ones Who Had Run Away.

And so she did.