Sunday, November 30, 2014

Sunday Sundries, 26

1. We had a quiet Thanksgiving, Joyce and I. Our son and his family went to the Macy's Parade, then up to western Mass. to be with my mom and my brothers and their families. Still, I got to share a meal with the one for whom I've given thanks for forty-five years (anniversary #45 on December 20!). We had a large turkey (which we'll be eating for a week or so--and then the soup) + smashed potatoes + homemade cornbread + homemade cornbread stuffing + homemade cranberry sauce + carrots glazed with honey (julienned by Joyce!). No pie. We a couple of cookies (okay--more than a couple) from the local bakery + some Italian lemon ice. (Pretty nice, lemon ice!)

2. We saw a couple of movies this past weekend: Horrible Bosses 2 (a title whose first word says all) and an Indian/Canadian film Dr. Cabbie, about a young Indian doctor who moves to Toronto, where he can't get licensed to practice medicine, so he becomes a cab driver and is soon treating patients in his vehicle (including a birth). Joyce and I were both disappointed, though. It had such a great premise, but the screenwriters dragged into their script about every film cliche you can imagine. Still, the principal actor (the doctor, played by Vinay Veimani) was appealing, there was some dancing that was fun to watch, and there were some moments of true and affecting emotion.

3, This week I finished Joyce Carol Oates' most recent novel (I think?), Carthage, a story about the murder of a young woman whose body is never found but whose accused killer, an injured vet of our Middle Eastern wars--a young man once engaged to the victim's sister--finds himself convicted and in prison. The novel spans about seven years and shifts the point of view around to let us see what most of the major characters are thinking and feeling (Oates is masterful at this--always has been). Some powerful themes emerge: family, love, war, our voracious media, our penal system--all come under Oates' powerful loupe. I had a few problems with some of it. At times, I thought, Oates wrote herself into a corner. A young woman, for example, doesn't use the Internet for a long time because her computer's crashed (this explains her ignorance about some important events), but Internet access is so pervasive (phones, libraries, etc.) that I just didn't buy it (also, this young woman is very bright--compounding the problem).

Still, I've loved reading Oates over the years. I began in 1969 with her powerful novel them (it won the National Book Award for fiction in 1970) and have pretty much kept up with her novels and short stories ever since. Every now and then I'll wait a year and find I have three more books to read--just to catch up!

She's a wonderful writer, one of our best. Why she hasn't won the Nobel Prize is a mystery to me.

4. I'm finally emerging from the deleterious effects of The Bug That Assailed Me on My Birthday (Nov. 11)--and from the effects of the wisdom tooth removal last Monday (the 24th). Yesterday and today have been the first two days I've felt anything like the energy I had before Nov. 11 (which, itself, was a pale shadow of my pre-Lupron energy). Here's hoping ...

Saturday, November 29, 2014

"I Can't Understand a WORD"

The other day--in the coffee shop (where else would I be?)--I overheard a sometimes intense conversation among some, uh, "veteran" folks (i.e., my age and older). They were talking about popular music today--especially hip hop and rap. Most of the conversation contained complaints about (1) the musicianship ("These guys can't even sing!") and (2) the lyrics ("I can't understand a word of it!").

That conversation, of course, has taken place in just about every generation since the birth of music. (Can you hear the Neanderthal father barking at his son who's pounding a log with a club (I'm translating freely now): "You call that rhythm! Why, in my day ..."?)

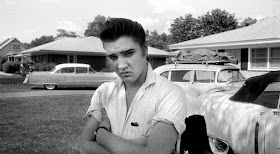

In my own youth, my parents were alarmed by (who else?) Elvis. Dad called him "Elvis the Pelvis" (I was not allowed to watch his movies) and, seeing P. J. Proby on one of those TV rock-and-roll shows (which my younger brother, Dave, was watching), he said (Mother was not in the room): "That's the first time I've seen teeth on a horse's ass."

Dad, I must say, had a fine tenor voice (more than fine, really) and had flirted with an opera career before that annoyance called World War II came along. As I remember (and my brothers may recall otherwise), I don't think he cared even for the swing era--Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, et al. Mom had similar tastes. Both would complain that they couldn't understand a word of the lyrics.

I should say, too, that the Hiram School (when I was in the junior high grades) was pretty well divided between the Elvis Camp and the Pat Boone Camp. (I--to my shame--was in the latter.) I secretly liked Elvis (he seemed ... naughty, a trait I admired in junior high school) but stuck with Vanilla Pat (I just made that up) in the Grand Debates about the better performer.

Later, I became a devotee of the Beatles (favoring them over the Stones, although I liked them as well--for the same reason I'd liked Elvis: Danger!), and the Woodstock musicians were really the last popular performers I loved. When Joyce and I saw the film Woodstock at the old Kent Theater (downtown), we loved it--as we did Let It Be, which we sat through twice (something I hadn't done since cowboy movies back in Oklahoma). We had albums by Crosby, Stills, and Nash and others of that era (we saw them perform in Cleveland right after May 4, 1970, and heard "Four Dead in Ohio" and "Find the Cost of Freedom" in their infancy). We also saw Dylan early on--he played his first set acoustic, then, after intermission, out came the electric guitars and bass.

But after that era, I sort of lost interest in popular music. I had a flurry of interest in Country (my roots, you know?), but turned away when most of it became irresolutely Right Wing.

A quick word about "musicianship." The folks I was listening to in the coffee shop have no idea, I think, how impossibly good you must be to rise to the top in the popular music world. I have an analogy--tennis. I used to play Early Bird out at the Western Reserve Racquet Club in Aurora. I could beat many of the men out there, but there were several against whom I had no chance. And those men had no chance against the club pro. Who had no chance against some of the pros in other clubs. Who had no chance in professional tournaments. Levels of excellence. Sometimes you can't really understand because you haven't ... played.

And as for understanding the lyrics? Well, the answer has always been this: The lyrics are not for you. So of course you can't understand them, not on any level.

That conversation, of course, has taken place in just about every generation since the birth of music. (Can you hear the Neanderthal father barking at his son who's pounding a log with a club (I'm translating freely now): "You call that rhythm! Why, in my day ..."?)

|

| P. J. Proby |

Dad, I must say, had a fine tenor voice (more than fine, really) and had flirted with an opera career before that annoyance called World War II came along. As I remember (and my brothers may recall otherwise), I don't think he cared even for the swing era--Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, et al. Mom had similar tastes. Both would complain that they couldn't understand a word of the lyrics.

I should say, too, that the Hiram School (when I was in the junior high grades) was pretty well divided between the Elvis Camp and the Pat Boone Camp. (I--to my shame--was in the latter.) I secretly liked Elvis (he seemed ... naughty, a trait I admired in junior high school) but stuck with Vanilla Pat (I just made that up) in the Grand Debates about the better performer.

|

| Guess who? |

|

| Pat Boone |

Later, I became a devotee of the Beatles (favoring them over the Stones, although I liked them as well--for the same reason I'd liked Elvis: Danger!), and the Woodstock musicians were really the last popular performers I loved. When Joyce and I saw the film Woodstock at the old Kent Theater (downtown), we loved it--as we did Let It Be, which we sat through twice (something I hadn't done since cowboy movies back in Oklahoma). We had albums by Crosby, Stills, and Nash and others of that era (we saw them perform in Cleveland right after May 4, 1970, and heard "Four Dead in Ohio" and "Find the Cost of Freedom" in their infancy). We also saw Dylan early on--he played his first set acoustic, then, after intermission, out came the electric guitars and bass.

But after that era, I sort of lost interest in popular music. I had a flurry of interest in Country (my roots, you know?), but turned away when most of it became irresolutely Right Wing.

A quick word about "musicianship." The folks I was listening to in the coffee shop have no idea, I think, how impossibly good you must be to rise to the top in the popular music world. I have an analogy--tennis. I used to play Early Bird out at the Western Reserve Racquet Club in Aurora. I could beat many of the men out there, but there were several against whom I had no chance. And those men had no chance against the club pro. Who had no chance against some of the pros in other clubs. Who had no chance in professional tournaments. Levels of excellence. Sometimes you can't really understand because you haven't ... played.

And as for understanding the lyrics? Well, the answer has always been this: The lyrics are not for you. So of course you can't understand them, not on any level.

Friday, November 28, 2014

Frankenstein Sundae, 73

Early in February, Betty wrote about her ongoing

frustration with the pace—and length—of her manuscript. She told me that she’d

gotten Mary Shelley only to 1831 (she would live twenty years more) but had

already written more than 1500 pages in her first draft. She saw no end in

sight—and she was worrying about all the revision

that would have to ensue.

And she was not feeling well—physically, emotionally.

She had some kind of infection that she was not recovering from—and her grief

about the recent deaths of her daughter-in-law and father was not abating. She

said she was now in the stage of anger

about those losses—anger at them for

leaving, anger at me for staying.

A week later—back from Massachusetts, where my

mother’s cataract surgery had been no

problem (not for me, I realize

now)—I wrote in admiration of Mary Shelley’s … what? … endurance? How she managed to keep going is astonishing,

I wrote. At 25, she’d buried three

children, suffered a near-fatal miscarriage, buried a husband, endured a

wrenching estrangement from her father …. For me (and my young readership)

this, I think is one of the principal messages: first surviving, then carrying

on.

Betty replied a few hours later, saying these last few days I feel as if I am coming

out of a strange world of loss & illness ….

A week later we exchanged Valentine’s greetings. I

told her about something I’d seen on America On-Line (remember that!), something called a “Valenstein”—sort of an anti-valentine, I said, complete with a Frankenstein-creature-face

in the shape of a heart. (I don’t think the idea caught on, though. Today—November

28, 2014—I had a hard time finding a Google Image of the thing.)

Later in February, we wrote back and forth a bit about

a recent review in the London Review of

Books of Miranda Seymour’s biography of Mary Shelley. Betty did not want to

read the review because, still at work on her own biography, she did not want

to be influenced by what Seymour had done. I told her that the piece had

praised her (Betty) highly, and I

sent her a couple of examples—here’s one:

She is also

able, largely thanks to Betty Bennett’s painstaking and brilliant recovery of

the history of Walter Sholto Douglas … [this is a story I will get into later] …

Betty replied a few hours later—Thanks so much for the quotes.

More than a month would pass before our next exchange.

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Thanksgiving, 1966

When Thanksgiving arrived in 1966 (November 24 that year), I was just completing my third month of my first year of teaching at Aurora Middle School. Seventh grade "Core" (English and American history). I had five sections of students, forty students per class. Do the math. I had just turned 22 (November 11) and was already beginning to wonder if I were in over my head. (Photo above is from the school yearbook that year.)

I was exhausted, all the time. I was overwhelmed with grading and preparations for class, and (I should confess--it's good for the soul, I hear) there were days when I walked in my room with only the vaguest idea of what I was going to do that period. Sometimes things went well. But then there were those other times ...

I was grateful that I had wonderful young men and women that year (those 12-year-olds from 1966 are turning 60 this year: think about that!). Some have stayed in touch over the years; some have found me (or I them) on Facebook recently. I had difficult days that 1966-67 school year, no doubt, but I'm certain that much of it was my own making. I was discovering what it meant to be a teacher. And it was a rough discovery.

|

| Mine looked like this, minus the fancy wheels and spotless exterior. |

By the end of each pay period I was eating boiled potatoes, smashed with margarine, sitting in a lawn chair (most of the furniture I had in my unfurnished apartment in Twinsburg was lawn furniture my parents had given me), trying to watch TV on the old black-and-white set (rabbit ears!) that my parents had given me when they got a new (flashy, color) one.

I was also lonely, profoundly so. That summer my parents had left Hiram (where we'd lived from 1956-1966) to take positions at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, about 700 miles away. My older brother was working on his Ph.D. at Harvard (or was he already teaching at the Univ. of Iowa? I don't remember), and my younger brother was a frosh at Harvard. My closest friends from high school and college had been scattered by the winds of grad school and marriage and Wanderlust, although a few remained at Hiram College (my alma mater), and I saw them as often as I could--which was not often. I had no money.

I had no love life. Zero. I'd had no real steady girlfriend for very long in college (Hiram girls were far too intelligent for that!), and most of the women on the middle school faculty were married or soon to be so. And because I was without money, I couldn't go out very often, and when I did, I found myself drinking beer alone--the brand called Self Pity. I soon stopped trying. I would not meet Joyce until the summer of 1969, nearly three years farther down the Heartbreak Highway.

As Thanksgiving approached, I knew I couldn't go out to Des Moines. Money, of course, was an issue (though I'm sure my folks would have helped out), but time was the real problem. School ended on Wednesday afternoon, and there was no way to drive 700 miles. Even I--in the deep Foolishness of Youth--would not have attempted it. And so I didn't. I figured I'd just sleep late, watched TV, eat some boiled potatoes. Maybe do a little schoolwork ... nah.

But early that week I got a phone call from Mrs. Ruth Rosser. Her husband, Ed, was on the faculty at Hiram College (chemistry), and the Rossers were among my parents' best friends at Hiram. The others were Paul and Rose Sharp, whom my folks had known since college days in Oklahoma. Paul Sharp was president of Hiram College. Anyway, our three families often got together for Thanksgiving, rotating venues. Dyers (5), Sharps (5), Rossers (4). The Sharps' three children--Bill, Kate, Trevor--were close in age to the Dyer boys (Dick, Dan, Dave). And I was in Marcia Rosser's class throughout junior high and high school. We all pretty much got along most of the time. In fact, it was fun. Ruth Rosser taught home economics at Garfield High School in Garrettsville (my mom taught high school English there, too), and her husband loved to cook, as well, so the meals were often awesome. It was fun to sit at the table and just listen to the conversations among some awfully smart and educated people. (At the time, I was not in that category: I could talk about the Indians and the Browns (the Cavs didn't exist yet) and any TV Western you could name. Impressive, eh?)

It was a different time, though. After the meal (which the women had pretty much prepared), the men went for a walk to smoke cigars while the women cleaned up. Oh, and we kids scattered to distant locations in the house, avoiding work if we could. If the weather was decent (it sometimes was), we played our "Annual Bowl Game"--touch football out in the yard. Or we watched Green Bay v. Detroit (on every year in those days).

So when the phone rang that day and I heard Mrs. Rosser's lilting voice (she made "Dan?" into several syllables), I was so happy to hear it. I think I had tears in my eyes already. And then she said that if I didn't have any plans--I? Have plans?--I was welcome to come to their house for Thanksgiving. I accepted with alacrity--and a deep gratitude. Not only did I know that I was going to eat the only decent meal I'd had since my parents moved away, but I knew that I was going to be in a very real way, home.

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Tony Hillerman

I'm not sure why I got to thinking about Tony Hillerman today. One thing I am sure of: It had nothing to do with Thanksgiving.

Or maybe it did. In our family, it's customary for folks to sit around and read during the holidays, and for some years it was pretty likely that one of us (at least) was reading the latest Tony Hillerman mystery.

Hillerman (1925-2008) was the author of a number of novels that take place in and around the Navajo reservation in New Mexico/Arizona border area. The stories featured Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, officers in the tribal police; all the stories featured Hillerman's fastidious research and knowledge of Navajo history, lore, and current situations. (Here's a link to his obit in the New York Times.)

I forget how I learned about the Hillerman series--probably from one of my brothers, fellow voracious consumers of mysteries. But once I read the first one (which one was it?), I devoured each of its successors while the printer's ink was still wet. And I was rarely, if ever, disappointed.

The first reference to Hillerman in my journal is from July 1998: to Learned Owl [book shop in Hudson], where I bought the new Tony Hillerman (The First Eagle) with the remainder of my gift certificate

I'm not sure why I had a gift certificate (?)--not near my birthday or other event--but it's clear from that entry that I'd already been reading him. I just checked our "Hillerman shelf," and it seems the earliest I read was The Fallen Man, published in 1996; my handwritten note in the front says "12/96." But perhaps I was reading him earlier; some titles, I know, I read in paperback, which I subsequently discarded and/or replaced with the cloth-cover edition. Anyway, I didn't begin keeping a regular journal until January 1997, so my "genesis story" with Hillerman is lost in the fog of time.

I met him once--quite by surprise and accident. It was Friday, June 5, 2004. My brief journal entry:

... in

the evening, we went to West Market, had dinner at Panera; then I walked down to

B&N and stumbled on Tony Hillerman, who was signing his KSU book of WW II

photos

Yes, in 2004, Hillerman published Kilroy Was There: A GI's War in Photographs with the Kent State University Press.

As my journal entry indicates, I had not known he was scheduled to be out at the Barnes & Noble on W. Market Street; otherwise, of course, I would have loaded a (big) shopping bag with all of his titles to have him sign.

So it goes in the book-collecting business.

I remember talking with him briefly about World War II--telling him that my dad had been both in Europe and the South Pacific. He said, "I bet he didn't talk about it much, did he?"

"No. Virtually never."

"That's true of so many WW II vets," he said.

And off I went, thinking I'd catch him at another signing one of these days. Which, of course, I didn't.

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Enid's Carnegie Library

As we note the birthday of Andrew Carnegie, I thought I'd post here a little segment from my memoir Turning Pages: A Memoir of Books and Libraries and Loss (Kindle Direct 2012). This tells about the opening of the Enid Public Library (a Carnegie), shown in the picture above--and reveals some of Enid's nasty racial history, as well. (I attended segregated schools. When we left Enid to move to Ohio in the summer of 1956--two years after Brown v. Board of Education--the Enid schools remained segregated.)

On Tuesday, 2 August 1910, the

opening of the new Carnegie library was front-page news in Enid’s ten-cent Daily Eagle. But on that page it was far from the only

story—or even the most prominent one. There was a political cartoon featuring

Teddy Roosevelt, a story about a judge making a campaign speech on the

courthouse steps. It was primary election day, and officials were expecting a

heavy turnout. There were stories about a miners’ strike, Iowa crop conditions,

the loss on 27 July of the revenue cutter Commodore

Perry in the Bering Sea. Three

youngsters had broken into a basement to steal beer, a vote on a ten-mill

school levy was imminent; there were a couple of local deaths, some children

had burned to death in a Philadelphia fire, and a drought was hurting folks in

nearby Guthrie …

For the first time in days, there

was no sensational story about Dr. Hawley H. Crippen, an English fugitive who

had fled by ship from Antwerp with Ethel Clara Leneve, his “typist,” after some

parts of the body of his wife, actress Belle Elmore, were found in the cellar

of his house. The cops nabbed him in Quebec. (A sensational trial and execution

would follow—as would a tasteless West End musical, Belle: Or, The Ballad of Dr. Crippen, in 1961.)

Inside the Eagle were stories about President Taft, ads for a remedy for weak

bowels, for men’s suits ($3.50), for a Model-T ($1000). A railroad timetable

showed the Enid–Denver roundtrip cost $20.85. Enid’s baseball team had squeaked

by the invaders from Salupa, Kansas, 1–0; the Damn Yankees had topped the

Tribe, 4–2.

But back on page one—on the far

right margin, below the fold—was the headline, with two sub-heads:

THE CARNEGIE LIBRARY

SPLENDID NEW BUILDING DEDICATED TO THE PUBLIC

PROMINENT MEN AND WOMEN PARTICIPATE IN SHOWING PEOPLE

THROUGH BEAUTIFUL ROOMS.

Several hundred people had toured

the building the previous day, the day of its opening. The

lobby, wrote the unidentified reporter, is

a large high ceilinged room artistically ornamented and decorated with palms

and pink roses. There was a

receiving line of current and former library board members. Local notables

conducted tours. Violinists sawed away in the fiery prairie heat. Punch was served. The library, the article concluded, is now open to the public and its pleasant environment furnishes an

ideal retreat for the wandering book lover on these summer afternoons and

evenings.

Unless you were black.

There would be no Carnegie Library

in Enid for African Americans to use—not for decades. In fact, few Carnegies anywhere welcomed them. (Louisville,

Kentucky, built a Carnegie branch for blacks only.) So Enid’s librarians later

modified one of the classrooms over at Booker T. Washington, the all-black

school in the all-black neighborhood south of Market Street. Took over some

books. It would have to do.

But, sadly, just sixty-two years later--in 1972--the city allowed the building to be razed. The last time I was in Enid (about ten years ago), I saw an empty lot ...

Monday, November 24, 2014

Dumber by One

I wrote on Facebook today that it seems as if every time I turn around, there's another painful medical/dental procedure to experience. Perhaps, I suggested, I should stop turning around.

I'm just back from having one of my final two wisdom teeth pulled. Apparently there was little problem, and the only pain I felt came from the shots designed to prevent pain. So it goes (as Vonnegut would have said).

So ... I'm now half as smart as I was before the surgery, right?

But while I was in the waiting room, I got the greatest news. I could not for the life of me remember an address where we used to live (I was only about three). After World War II, my dad began working on his Ph.D. at the University of Oklahoma. For a year we lived in Norman (our "real" home was in Enid, 117 miles north---so swears GoogleMaps).

I've tried various things to find that address in recent months--Ancestry.com, contacts with local historical societies, etc. No luck.

But today--while I was waiting to have my wisdom reduced--I got an email from the Norman Public Library. In a city directory from 1947 they found the Dyer name and address--428 Park Drive. I just looked at the "street view" on GoogleMaps and recognized the house immediately though I could not have told you a thing about it just moments before.

It's still there--that's the best news. I'd feared that Sooner campus expansion might have devoured our house. But, no. The campus lies a block or so south of our place, and we're safe. Or someone is. I haven't checked yet who the current residents are.

I'm hoping this spring (if my jaw has healed, if some other odious thing has not happened to me) to take a "sentimental journey" back to the places we lived in the Southwest--Enid and Norman (OK), Amarillo (TX)--and interview the folks who are living in "our" houses now. Sound like fun? It does to me. More fun--say--than oral surgery?

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Sunday Sundries, 25

1. We love Last Week Tonight with John Oliver on HBO (show is now on hiatus until February). It's comedy, yes, but also deals with political and social issues that the major news networks ignore, for they are too busy with stories about Ebola and other matters whose principal virtue is that they frighten viewers. (Here's a link to a YouTube video of his piece on lotteries.)

2. Earlier this week, I wrote about my memories of one of my mentors, George Hillocks, who died this week. I said in that post that I'd given away the book he'd co-authored, The Dynamics of English Instruction, Grades 7-12. Guess what? It turned up in one of the piles we're trying to deal with (new shelves, donations, sales).

|

| My Copy! |

As I read through it now, I find all kinds of insights that I probably indicated were my own when I was teaching. Yes, the text is a bit dated now (1971!), but it remains the single most thoughtful and comprehensive text I know on teaching English. I'm grateful that I got to tell that to George Hillocks only a few years ago.

3. An Exciting Friday Night: Still not completely recovered from the Bug That Bit Me on My Birthday, I've been unwilling/unable to go outdoors much. I usually make it to Open Door Coffee Co. in the morning (a couple of blocks from our house--a nice walk, except for Saturday, when Black Ice reminded me at every step of my mortality). But that's been it since last Wednesday when we got back from Pottsville, PA, on our mission to deliver our John O'Hara collection to the Schuylkill County Historical Society. But Friday night we ventured out--though we did not leave the car (I kept my slippers on--an Old Man move for sure). We went to the Starbucks drive-thru in Stow-Kent, where, during our last visit, they had presented me not with the venti decaf Americano I'd ordered but with a pumpkin spice latte, an error I did not discover until my first sip--about halfway home; we turned around, got a replacement and a we-screwed-up card from Starbucks that saved us $4 on our order on Friday night. After we got home, I lit the gas logs in the living room for the first time this year, curled up and read and wrote for an hour before heading upstairs for a Wallander episode. (Are you still awake? I'm not sure I am, and I'm writing this!)

4. Finally, I want to recommend Brock Clarke's latest novel, The Happiest People in the World (a title that may win the Irony Award this year!). I first encountered Clarke's work when I read his 2007 dazzler An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, a novel I liked so much I settled in and read all of his previous works:

4. Finally, I want to recommend Brock Clarke's latest novel, The Happiest People in the World (a title that may win the Irony Award this year!). I first encountered Clarke's work when I read his 2007 dazzler An Arsonist's Guide to Writers' Homes in New England, a novel I liked so much I settled in and read all of his previous works:

- What We Won't Do (short stories), 2002

- The Ordinary White Boy (novel), 2001

- Carrying the Torch (short stories), 2005

I reviewed Arsonist's for the Cleveland Plain Dealer (Sept. 2, 2007) and then his next novel, Exley (2010) on Nov. 7, 2010 (link to that review).

I got to meet Brock after arranging for him to spend a day with our students at Western Reserve Academy in April 2008. At the time he was teaching creative writing at the University of Cincinnati (he's now at Bowdoin), and he drove up on Sunday evening (April 27) and had supper with the English Department. He was a hit with us and, the next day, with the students. He spoke to our Morning Meeting and then visited classes all day and then attended a reception hosted by one of our parents' groups--the Pioneer Women, who had funded his visit.

I see I'm running out of space, and I'll have to talk more about his new book in a post later this week. But I thought you'd like to read the introduction I delivered when he spoke to Morning Meeting that day in 2008, so here 'tis ...

Last spring I was paging through a

recent issue of Kirkus Reviews,

looking for a forthcoming book I might like to review for the Cleveland Plain Dealer. My usual pattern when I do this is to look for

writers I’ve heard of—writers I like. I don’t enjoy writing negative reviews and

know that good writers usually—though certainly not always—write good

books. I think of Hemingway’s Across the River and into the Trees and

Jack London’s Michael, Brother of Jerry

as two of the worst books I’ve ever read, both by very good writers.

Anyway,

last spring, paging through Kirkus, I

came across a novel with a strange title by a writer I’d never heard of. An

Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England by Brock Clarke. I skimmed the very positive Kirkus review (just skimmed—didn’t want to influence my own thinking too much!) and

decided: This is the book for me! Not only did the story sound engaging—a

high-school boy accidentally burning down the home of Emily Dickinson (in the

literary world, a heinous act comparable to, say, converting this very chapel

into a Chipotle—though Mr. Gough, I know would love THAT)—but the story

involves arsonous assaults on a number of other New England literary landmarks,

including the homes of Mark Twain and Robert Frost. Writers I teach! Writers whose homes I’ve visited! Writers whose graves I’ve knelt beside and

wept! (Yes, I’m one of those.)

The Plain Dealer was willing to assign me

the book, but before it arrived, I ordered and read Brock Clarke’s previous

three books—another novel (The Ordinary

White Boy) and two collections of short stories (Carrying the Torch and What

We Won’t Do)—and was greatly impressed with his range, his sense of humor,

his ability to coax from ordinary experiences some most uncomfortable truths

about our lives. I laughed when I read

Brock Clarke, and when I read that story “Starving,” a story a number of you

have also read, I cried (yes, I’m also one of those).

And then

the galley of Arsonist’s arrived; I

read it late last June; I loved it. I

wrote the review, sent it to the PD, and they ran it on September 2, right

about the time the book was released—and I soon discovered that I was just one

reviewer among many who loved the

book. The New York Times, Chicago

Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post—these and many other

publications ran rave reviews of the sort you rarely see these days when it’s

more fashionable to trash than celebrate a book.

I knew,

too, that I wanted my students to

read it—near the end of the year when they would be more familiar with many of

the allusions Brock Clarke makes in the novel—allusions to The Scarlet Letter to Emerson to Frost to Twain to so many other

American literary figures—and to one very special non-American, a non-muggle, in fact: Harry Potter.

And I knew

that I wanted to have Brock Clarke visit WRA.

I found him on the website of the University of Cincinnati, where he’s

taught writing and literature for seven years (after other teaching experiences

at Clemson and the University of Rochester, where he earned his Ph.D.), and on

the Cincinnati site I learned, too, of his many previous literary awards

(Pushcart Prizes among them), his publications in some of the most prestigious

literary journals in the country (Virginia

Quarterly Review, New England Review,

Missouri Review, Southern Review, Georgia

Review).

I e-mailed

him to see if he does this sort of thing—visiting high schools, meeting with

students. He responded quickly: Yes, he

does this sort of thing, and he would love to come here. And my next move was to approach the Pioneer

Women, who have for so long supported so many different activities around the

school—including financing the visits of and holding receptions for several

other prominent writers, among them Tobias Wolff, Matthew Pearl, and Sharon Olds. The Pioneer Women were eager; they were

generous; they are the principal reason that we have with us today a young

writer whose Arsonist’s Guide has

been swirling our American literary waters, a young writer whose works—past and

future—will, I am confident, one day assure his place among those very folks

whose homes are torched in this funny and wonderful—but also very

wrenching—novel.

Please

welcome to this school (the school where the grandfather of Emily Dickinson

once worked) and to this podium (the podium where Ralph Waldo Emerson himself

once spoke) … writer Brock Clarke.

Saturday, November 22, 2014

John O'Hara: Photographs

These pictures designed to accompany my publication, "Do You Like It Here?": Inside the Worlds of John O'Hara, Kindle Direct, 2014.

1. O'Hara's birthplace: Pottsville, PA; 123 Mahantongo Street

2. Boyhood home; Pottsville, PA: 606 Mahantongo Street

3. O'Hara farm, near Cressona, PA, their "summer place"; Panther Valley Road & the old farmhouse.

4. St. Patrick's School; Pottsville, PA

4. St. Patrick's School; Pottsville, PA

5. Home of his mother, Katharine Delaney O'Hara; Lykens, PA

6. Keystone Normal School; Kutztown, PA (now Kutztown University of Pennsylvania)

7. "Linebrook": His final home in Princeton, NJ

8. Grave--Princeton Cemetery

9. "O'Hara Nook": Pottsville Free Public Library

10. John O'Hara Street; Pottsville, PA

11. YMCA; Princeton, NJ; September 2012

John O'Hara--Now Available

My long essay/booklet on John O'Hara, a piece I'm calling "a brief biographical memoir," is now available on Kindle Direct for the whopping (low) price of $2.99. (You can read it on your smart phone or tablet if you download the free Kindle app.)

The publication is the result of several years' work. Below, I've reproduced the Foreword and some of the other front matter. Note, too, that in a separate posting today I'm providing photographs of some of the key locations I mention in the publication.

Dedication

To Prof. Abe C.

Ravitz

Who, during my years

at Hiram College (1962–1966), showed me a brave new world, gave me some of the

maps I would need to explore it, and wished me bon voyage.

And

so it has been …

Foreword

What follows is an account of my

recent pursuit—consuming several years—of John O’Hara, 1905–1970, a writer who

at the height of his long, controversial career enjoyed bestseller status and serious,

if mixed, critical reception. This is a personal story—a memoir of my (mild?)

obsession—although I necessarily include lots of information about O’Hara’s

life and career, about his books, essays, plays, and journalism.

It’s important to note what this

publication is not. As its very

brevity certifies, this is neither a comprehensive biography (there are many

aspects of his life I do not explore—or even mention) nor a close reading of O’Hara’s

many works. Although I do sketch some of the details of O’Hara’s life and some

specific works, I urge readers who are eager for more to consult the

biographies listed in the bibliography. Mine is an account of a curious

tourist, one who pauses to look closely at things that interest him, then moves

on.

This piece is full of a tourist’s

opinions, as well—my assessments of his work, of his life, of his writing’s ultimate

value. Positive and negative. I realize, of course, that no one has the Final

Word on anyone else, and this effort does not pretend to be definitive. Other

readers will have other opinions, will wear other lenses through which to view

this most remarkable man—and story. Despite some negative things I say here, I’ve

greatly enjoyed my journeys through O’Hara’s work, my explorations of his

worlds. And I am grateful for those who supplied directions, comfort, and

encouragement along the way.

Friday, November 21, 2014

Frankenstein Sundae, 72

In Mary Shelley’s life there are many moments I wish I

could have witnessed. Shelley’s courtship of her, the Frankenstein summer, and on and on. But one of the most intriguing,

for me, was early in 1822 when she and some significant others were gathering

in Pisa: Byron, Thomas Medwin (Shelley’s college friend who would later write a biography of the poet), Edward John Trelawny (a rake of the first order who

entered the orbit of thttp://old.post-gazette.com/books/20030914oharaside0914fnp2.asphese powerful stars and enjoyed the glow). Trelawny would

outlive almost all of them—and would arrange (he died in England) to have his

ashes buried alongside Bysshe Shelley in Rome. On his stone are some lines of

Shelley’s, lines he wrote shortly before he drowned:

These are two friends whose lives were undivided.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bone be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

So let their memory be now they have glided

Under the grave: let not their bone be parted

For their two hearts in life were single-hearted.

Anyway, in Pisa these folks were always looking for

novel things to do. Here’s what William St Clair (one of Trelawny’s

biographers) wrote about this epoch:

On a typical day

the men would practise boxing or fencing or shooting. Byron would travel the

400 yards to the city gate in his carriage to avoid being stared at, and then

mount his horse and ride a couple of miles with the others …. The evenings

would be spent in visiting or at the theatre …. On one occasion Byron proposed

that they should themselves act Othello

in the great hall of his palace (Trelawny, The Incurable Romancer, 1977, 59–60).

We know some of the assigned parts. Byron was Iago

(appropriate); Edward Williams (who would drown with Bysshe that summer),

Cassio; Medwin, Roderigo; Desdemona, Mary Shelley; Emilia, Jane Williams. They

rehearsed a few times, but the project collapsed because of the complaints of

Countess Teresa Guiccioli—Byron’s latest squeeze—who spoke no English and felt

excluded. I suspected that the mid-April arrival in Pisa of Claire Clairmont—mother

of Byron’s illegitimate daughter—was a factor, as well.

On January 27, 2001, I wrote to Betty: Don’t you wish you could have witnessed one

of those Othello rehearsals with MWS,

Byron, et al.? Oh my.

She replied fifteen minutes later but did not respond

to my question. Mostly she rehearsed for me some of her many activities—from

teaching, to going to meetings, to reading, to ….

I wrote back a week later to tell her I was heading to

Massachusetts to help my mom, who was about to undergo cataract surgery. (As I

type, I’m remembering my own recent visit to my eye doctor, who told me

cataracts were forming in my eyes

now.) I also said that in my own account of Mary’s life I’d reached the

point—the awful point—of the drownings. I

have much sadness to write about in the ensuing days, I said.

Thursday, November 20, 2014

George Hillocks, R.I.P.

Every so often I receive from the National Council of Teachers of English its online newsletter called "Inbox." I usually skim it, occasionally read something--follow a link somewhere. But on November 18, I was shocked to see the following:

George Hillocks Jr. Has Died

|

Educator, author, and researcher George Hillocks Jr., professor emeritus in the Departments of Education and English Language and Literature at the University of Chicago, passed away on November 12. He also had taught writing in Chicago schools for more than 25 years.

In 1997 Hillocks won the NCTE David H. Russell Research Award forTeaching Writing as Reflective Practice. In 2004 he received NCTE's Distinguished Service Award. Of Hillocks's 1986 NCTE book, Research on Written Composition: New Directions for Teaching, former NCTE Executive Director James Squire called it "a splendid piece of work that needs to be considered carefully and soon."

As you can tell from the item, he was quite an accomplished scholar. But he was more. To me he was a connection to one of the men who had the greatest influence on me early in my teaching career--Bernard (Bernie) J. McCabe.

I met McCabe at what was then called the Educational Research Council (ERC) in Cleveland (1957-1984; link to brief history of ERC). Schools that were members of the Council (as Aurora was) got all kinds of services from them--including workshops for teachers--in the summer and during the school year. And it was at one of those that I met McCabe--a crusty, brilliant man whose abrupt manner annoyed some but inspired others (like me). I attended a number of his workshops, but the most influential was one on film study and filmmaking with students (late 1960s? early 1970s?). I dashed back to Aurora and was soon teaching kids about film history--and "supervising" them as they ran all over the place shooting their own films.

McCabe occasionally spoke fondly of a former colleague--George Hillocks--with whom he would write what I long thought (still think?) was the best book for English teachers I'd ever read: The Dynamics of English Instruction, Grades 7-12 (1971--a third author was James McCampbell, whom I never met). I had this book for years, consulted it often, stole from it routinely, and only recently (wouldn't you know!) gave it away during our current Downsizing Frenzy. I wish I had it right now ...

Joyce and I met George Hillocks many years ago at an NCTE function (I can't remember where or when--it was in my pre-journal days), and we talked a lot about Bernie. I remember thinking they sounded a lot alike: the nasality, the keen intelligence, the eruptive laughs.

On May 1, 1975, not long after I arrived at school, my principal, Mike Lenzo, called me into his office. Showed me a story in the Plain Dealer. "Lakewood Couple Found Shot to Death" says a headline. Bernie. A double suicide. He was only 45; his wife (a first grade teacher), 42. No note. No reason given.

Years later (2010 or so), writing my memoir about my teaching career (Schoolboy), I wanted to know more. So I found George Hillocks' email address and exchanged a few messages with him about Bernie. But he didn't really know a lot more--or was not going to share what he did know. But he said he missed Bernie--a lot. (I'll add that I never again taught Edwin Arlington Robinson's suicide poem, "Richard Cory," without thinking about Bernie McCabe. Link to the poem.)

And now George Hillocks is gone as well. Two titans in the profession. Irreplaceable.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Frankenstein Sundae, 71

Then, four days later, on December 14, Betty wrote to

tell me that her father had died. She mentioned that he and her mother had been

happily married for more than sixty-eight years—in the deepest bond of love. Betty’s is a very emotional note and

mentions her crying—I will stop again

soon, she said.

Having recently lost my own father, I had a sense of

what she felt. The worst feeling I have

experienced this past year without my father, I wrote, is an overpowering sense of his absence. I wrote in my journal last

year [the day he died] that I was going to bed for the first time without a

father and would wake up in a world without him. It was a desperate, lonely

thought, and I have not recovered and not hope to recover.

What I meant by that last part: I do not ever want to think of my father and not feel his loss—painfully feel it.

A few days later I wrote to tell Betty that Tennyson’s

ode to Wellington, which I’d just read, was one

of the worst poems ever written. It’s too long to reproduce here, but

here’s one of the early stanzas:

II

Where shall we lay

the man whom we deplore?

Here, in streaming

London’s central roar.

Let the sound of

those he wrought for,

And the feet of

those he fought for,

Echo round his bones

for evermore.

I added in that same note that I had a sort of self-imposed deadline

for the end of my first draft. Betty replied the next day. Here I am plodding away, she said. I continue unnaturally worn out—so you keep writing for the two of us.

I’m incredibly touched as I read those words now—you keep writing for the two of us. She

had begun to accept me—not as an equal (she had none) but as a colleague,

someone also doing what she considered the Good Work of trying to tell Mary’s

story fairly, completely.

My reply, though, mentions none of this. Instead, insensitive,

I wrote about my recent interest in the actor Edmund Kean (one of Mary’s

favorites) and told her I’d collected a

few Kean items over the years. Our correspondence drifted back to him in

mid-January 2001. I finished that last

bio of Kean, I wrote. What a sad

story (as all ultimately are). Dead at 45—destroyed by alcohol …. But during

his last appearance on stage, he collapsed into the arms of his son, Charles.

Not a bad way to go, I guess.

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

"I Just Dislike Shakespeare"

In a recent Facebook comment, a former student from long ago confessed this: "I just dislike Shakespeare ... I just feel disdain and general ugh." She wrote the note apologetically: She knows I love the Bard. I'm continually posting things about him on Facebook, and I've written a YA biography of him--All the World's A Stage: The Worlds of William Shakespeare (Kindle Direct, 2012). (Link to the book on Amazon.) Last year I wrote a series of blog posts about my slow, growing affection for the Bard that resulted, after many years, in my seeing all of his plays onstage, a quest that took Joyce and me many, many places.

Yes, as I wrote in those pieces, I hated him, too. We read Julius Caesar and Macbeth in high school, and I could understand virtually none of it. I could not comprehend why he had such a global reputation, why everyone seemed to think he was a genius, the best writer in the English language--Hell, he doesn't even use English!

It was no better in college. I read Macbeth again in English 101 (hated it--the play, not the class), then majored in American literature, my subtle way to avoid any courses about Shakespeare, a way eased by the absence my senior year of the professor who taught those courses (sabbatical leave).

After I graduated, I began my career in a nearby middle school (where I met the young woman who wrote to me today) and proceeded to avoid Shakespeare for some years ... though I read some of the plays on my own (Hamlet was one of them), just to see. Reading him slowly--without tests or papers on him hanging over me like the sword of Damocles--was better. I slowly (slowly) started to "get it."

In the 1985-1986 school year I decided to use The Taming of the Shrew with my 8th graders. I figured they would like the war-between-the-sexes stuff (which can rage in middle school), the young lovers stuff (which can rage in middle school)--and I knew they would love the Zeffirelli film with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (they did).

In the early 1990s I switched to Much Ado About Nothing because of the wonderful Kenneth Branagh film just released--with Emma Thompson, Kate Beckinsale, Denzel Washington, Keanu Reeves, Michael Keaton, Robert Sean Leonard, and numerous other notables. (The kids liked that film, too!)

By then--by the mid-80s--I was a Shakespeare fanatic: I'd read all the plays (many multiple times); seen many productions, many films; read many books about the Elizabethans, about Shakespeare. I went to Stratford-Upon-Avon and other relevant places. I often took groups of kids to see plays and films in Cleveland and elsewhere.

And I learned something I probably should have known but didn't: The more I knew about him and his world, the more I enjoyed the plays. And they are plays--meant to be seen and heard, not read. Great actors bring life to the words--can help you understand even when you don't know what the words mean.

I've often said/written that if Shakespeare were somehow to materialize today in a middle school cafeteria somewhere and sit with a group of 8th graders, he would understand virtually nothing about what he experienced--the language, the clothing, the food, the smells, the sounds, the devices (electronic and otherwise), the lights, the clocks--none of it. If he hoped to communicate with those young folks, he would have a lot of learning to do first.

And we are in the same situation. If we want to understand him, we have some work to do, too, in learning about his world--and I can tell you that it's endless work. But--for me--well worth it. More than well worth it.

So ... Facebook friend from decades past ... I feel your pain. I once knew it intimately. But things can change ...

Or not.

I don't like every celebrated writer whom I'm "supposed" to like. Maybe one day I'll do a post here about the most famous writers I can't stand!

Monday, November 17, 2014

Frankenstein Sundae, 70

Scholar Betty Bennett had written to me with some worries about a new biography of Mary Shelley that had just appeared ... would it be better than the one she was working on? I had replied with what I hoped was encouragement--but was it just patronizing?

Betty replied twelve minutes later.

Fortunately, she recognized my genial intent rather

than my presumptuousness: Thanks so much

for the (much needed) pep talk—and all your kind words.

Whew.

On October 23, Betty wrote about her computer

problems. She was still using MS-DOS and asked what word-processor I used. She

knew it was time to change systems—but didn’t know how to proceed.

I wrote back right away, telling her that I hated

Microsoft Word (I did) and preferred

WordPerfect (I did)—and gave her the

reasons. I told her that I did have Word on my machine, though, because some of

my publishers (Kirkus, for example)

preferred that format. I offered my help whenever she needed it during her

transition.

She replied that she felt too uncertain to change

programs until she’d finished her book.

Then, for a reason I cannot figure out from our

correspondence, a month-long silence ensued. I broke it: How have you been? The rest, I wrote on November 27, was a newsy

note, telling her about our Thanksgiving plans (scotched by snowy weather in Buffalo). We had planned to join the

family in Massachusetts, but we ended up, just the two of us, Home Alone with

Mr. Turkey. I also moaned about the 2000 election, Bush v. Gore, etc.

Betty wrote back promptly with an account of her busy

month—research, meetings, family visits. Glad

to catch up—& again be in touch, she said at the end. And in early

December she wrote about the failing health of her father, who was 95, the age

of my own mother as I type these words

in November 2014. She signed off playfully: Your

migraned friend …

I wrote back about the still-recent death of my own

father in November 1999—too many “firsts”

without my dad: my birthday, Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s. He had a

wonderful tenor voice, and when I hear carols I cannot help but think of him,

and I weep at the most awkward times (like when I’m sitting in Starbucks and

trying to read—or walking along in a mall).

Then, four days later, on December 14, Betty wrote to

tell me that her father had died.

.JPG)

.JPG)