That's right--Elmer, not Elmo.

The other day--for what reason I cannot imagine--I remembered, years ago, that I'd read some stories in Boys' Life about a worm named Elmer. This was a wise worm. A kid (whose name I couldn't

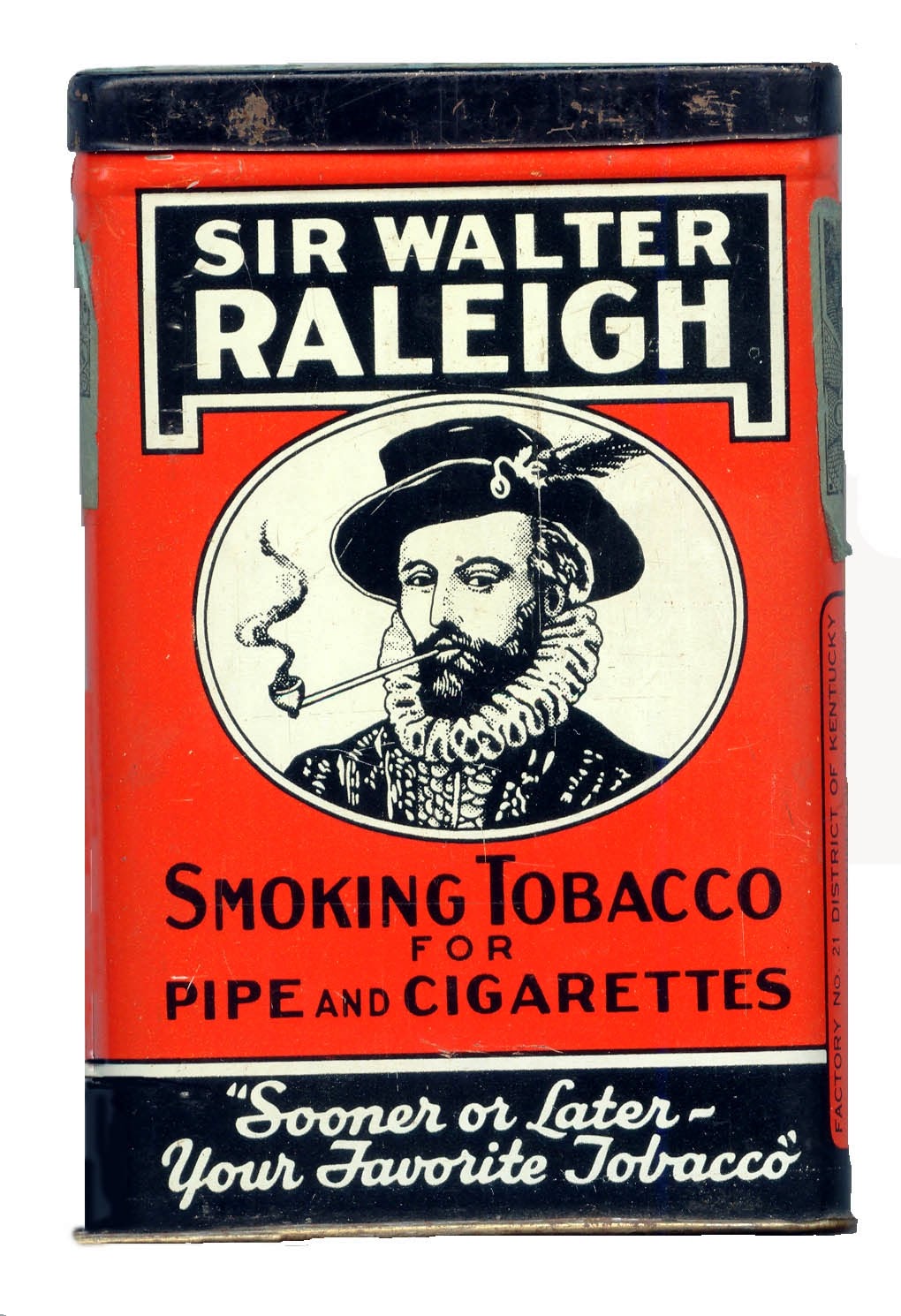

recall) kept him in a tobacco tin (remember those? my father had some around the house). From that tin, Elmer was somehow able to help him with his homework and other odious tasks. That's all I could remember ...

So, I decided to find Elmer, a task that Google accomplished for me in seconds. It seems there were four of those stories, all written for Boys' Life by Ned Ellis. Here's the list Google found for me:

ELLIS, NED

- * Elmer Goes To the Party, (ss) Boys’ Life Oct 1966

- * Elmer Joins the Dropouts, (ss) Boys’ Life Apr 1966

- * Elmer Works for Santa Claus, (ss) Boys’ Life Dec 1956

- * Elmer, the Worm, (ss) Boys’ Life Mar 1959

But 1956? 1959? Definitely. I was in junior high and high school then--and although by 1959 I would not have been carrying Boys' Life around with me, I think I was still subscribing to it, still reading and browsing when I didn't feel like doing my homework--which was most of the time.

As I looked at the list of Ellis' "Elmer" stories, I didn't remember the one about Santa Claus, so I got on eBay and ordered the March 1959 issue of Boys' Life, the issue pictured at the top of this page. (I was unable to locate a digital version of it online.) When it arrived the other day, I promptly read the "Elmer," realized that, yes, this was what I remembered (sort of), and then spent some time flipping other pages ... remembering.

In March 1959 I was fourteen years old (would not be fifteen until November) and was in ninth grade. That seems a little bit too old for Boys' Life, but I was, let's say, slow to blossom? I was an immature ninth grader (just as I am now an immature Senior Citizen), so I was still reading Boys' Life at home (if we indeed still subscribed to it)--or in the Hiram High School Library, which sat up in front of our large study hall in the top floor of our long-ago-razed Hiram High building. This picture from an old yearbook gives just a hint of the arrangement. You can see a few of the reference books in the front of the room; magazines--including Boys' Life--were in racks whose backs appear to form a wall at the front of the room. That area up there was our entire junior high and high school library.

There were ads all through the March '59 issue for Scouting equipment: tents, lamps, hatchets, knives. There was an ad for Spalding (sporting goods) that featured a picture of Yankee catcher Yogi Berra (my hero at the time--I was the catcher on the Hiram Huskies' team). There were feature stories--about architecture, blimps, knot-tying. Ads for .22 rifles, flutes and piccolos (by Armstrong of Elkhart, Ind.), a running comic strip I'd forgotten called "The Tracy Twins," by Dik Browne, artist for "Hi and Lois." Goodyear Tires, Passover and Easter, a cartoon called "Rocky Stoneaxe," a feature on kite-flying, an ad for Wilson baseball gloves, for pimple treatments. A feature on hula-hooping, stamp-collecting, fishing, climbing a rope ladder, a big ad from Clearasil called "What Girls Think about Boys Who Have Pimples," supposedly written by Kay Rogers, "popular student at Harding High School" in Oklahoma City. (Popular Kay Rogers liked boys who didn't obsess about their pimples but who did something to deal with them--like apply Clearasil, a substance, by the way, which never worked for me; only Time did.) And much more.

I'd forgotten a continuing feature--"Think and Grin"--appearing on the final page. Jokes sent in by readers. And "daffynishions"--e.g., "Permanent wave--a girl making a career of the navy." Here's one of the jokes:

New Husband: My wife treats me like a Greek God. At every meal I get a burnt offering.

And another ...

Teacher: Give me a sentence with an object in it.

Pupil: You are very beautiful, teacher.

Teacher: What is the object?

Pupil: A good grade.

And, of course, the Elmer story ...

TO BE CONTINUED ...

.jpg)